The wreckage is growing.

Returning to Milieux on April 9, the space had been re-worked since my last visit on April 4.

That previous visit was to witness the first phase of UKAI Projects’ Shipwreck residency, which invites artists and community members to build a home amidst ruins — ruins dispersed around the newly-renovated Milieux Commons.

The first Phase saw UKAI Projects bringing in materials to begin shipwrecking the environment, adding gelatinous creatures, glitching video auctions and noisy eco-fascist robots into the landscape. At that time, I noted that the works seemed separate from each other, individual interventions into a still fairly pristine university setting.

Now, though, the setting itself is beginning to transform, the lines blurring between what was there before and what has come to be.

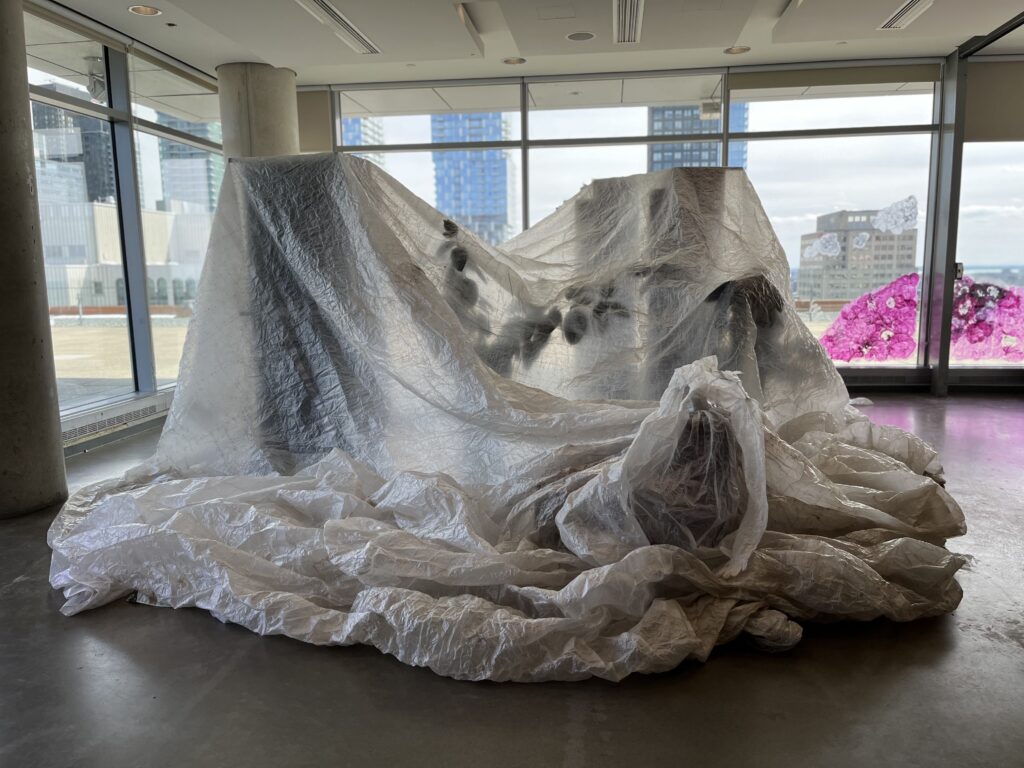

The common space on the 11th floor, where students often come to lounge on couches during free time, has been taken over by a make-shift greenhouse. A giant tarp covers the couches, repurposed into load bearing instruments, creating a humid space for plants to thrive.

Looking past the tarp, the windows surrounding the space are newly-covered in pink swirling designs, like memories of magenta clouds or maybe poisonous bushes, blocking visitors from seeing through to the outside world, or the outside from seeing in.

There are new assemblages, too, dotted throughout the space: a discarded piece of rubber curls on the ground, housing a feathered carcass.

A large rock serves as the base for a slender branch, extending upward, while both are sheltered by a sideways laptop, hugging their formation.

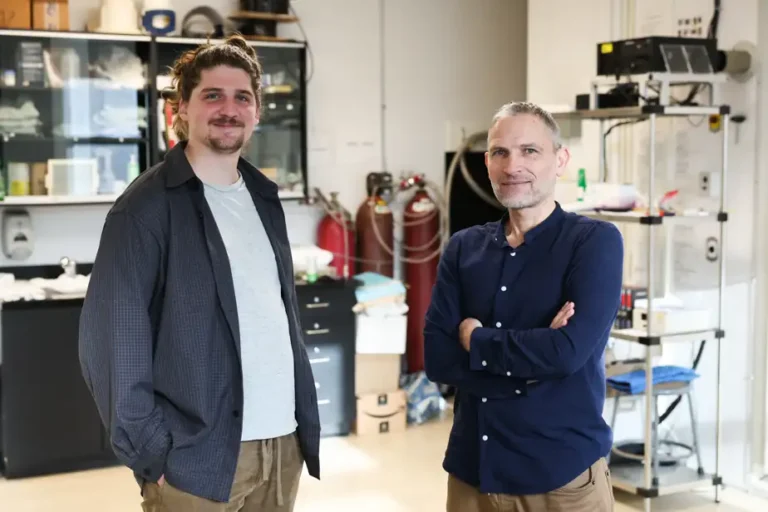

These are the interventions of three local artists: Meghan Moe Beitiks, Eija Loponen-Stephenson and Gabriel Junqueira, who have spent the last three days bringing their art into the space, interacting with each other and with Milieux itself, to let something bloom.

Junqueira is a multi-media artist who explores the relationships between body, technology and ecology. He spent the two weeks leading up to the residency wandering Montreal’s in-between spaces, seeking discarded objects that might be ripe for repurposing. Wandering parking lots, highways, factories, he gathered material for Milieux.

On the first day of the residency, he says, he brought in his shells, metal parts, and bones. That sparked a curiosity in artist Eija Loponen-Stephenson, who returned the next day with her own found objects.

That became the foundation for a dialogue between the two artists, who had never met before.

“‘It was quite a good match,” Junqueira says.

“It was very playful and intuitive,” Loponen-Stephenson adds. “I also feel like we got to know each other through our objects.” She says she tends towards industrial objects that mimic nature, but Junqueira’s use of the organic was inspiring.

The two worked with the space, rather than trying to distance the project from its institutional setting. The assemblages littering the Milieux Resource Room include office stools and Milieux plants, so that the room bears a kind of diagonal relation now to its original function.

“It kind of merged with the context we tried to create in here,” Junqueira says.

“You think about the [university] as a place of learning,” Loponen-Stephenson adds. “I feel like we turned it into a different place of learning, like a museum or something. Instead of things being explained they’re being shown.”

Over the course of the artists residency, even the original works UKAI had dispersed were up-ended. Luisa Ji’s gelatinous creatures had to be moved to a different station in the space, meaning they were more exposed to sunlight.

The jelly has melted and hardened. Where before the creatures looked like signs of life on a shipwrecked island, now they seem to serve as a warning.

Behind them, Meghan Moe Beitiks’ paintings swirl on the windows, lending a sense of playful intensity to the environment. Using chalk marker, Beitiks’ has provided some notes on the work: 500 ml of water-based paint, dish soap, and water drunk by the artist.

The sounds of the artist drinking are fed back into the windows via a propped up speaker, emphasizing the cyclicality of consumption. An asterisk on the wall notes that 500 ml is also the amount of water used by 10-50 Chat GPT queries.

These works get at questions of resources and use: when materials are finite, how do you re-purpose them? In a hostile setting, how do you adapt the objects you know into assemblages you don’t?

What kinds of use are valuable, what kinds are wasteful?

Rather than Milieux fading into the background of a “chaos of work,” as UKAI’s Jerrold McGrath put his hopes for the residency, Milieux is front and centre here. Artists are adapting to it, reshaping it, learning what can and can’t be changed.

Introducing a walk-through of the artists’ works, UKAI’s Kasra Goodarznezhad told the crowd: “There’s no, not really limitations,” before pausing. “Obviously, we ask that you not destroy any of the works.”

The room laughed, before Milieux’s Marc Beaulieu clarified a few other parameters: no tape on the painted walls, no tech in the front room, which is unsecured at night.

“It was challenging,” Junqueira says of the space. “Some of the existing infrastructure was very distracting,” Loponen-Stephenson adds.

She was surprised by just how disruptive their time in Milieux turned out to be. Repurposing the couches from the entrance space for her greenhouse left some students disgruntled.

“The main entrance area is definitely used as a place of refuge for students and privacy. There was a lot of couples who came up here to make out and they were really upset about the fact that the couches were no longer useful in the way that they wanted them to be useful,” she explains. “Getting that indignant reaction was really surprising.”

To rework the purpose of an object or a material is also to take something away.

The next phase of the residency invites Milieux community members to bring in their own additions to the shipwrecked environment. Beitiks has left chalk markers for participants to respond to their window designs; Junqueira and Loponen-Stephenson have set out a table with extra found objects, to be distributed through the assemblages by new visitors.

At the walk-through, community members seem initially hesitant. It’s hard, perhaps, to feel like intervention is allowed in an institutional setting. But small contributions begin: Miranda Smitheram, of the Textiles and Materiality cluster, brings a rock into the assemblages. A couple others pick up markers. Bit by bit, the individual works become something collectively salvaged.

“At the same time that it’s a pretty dystopic image, there’s also a utopia going on,” Junqueira muses.

“It can be the end of something or the beginning of something else.”

From April 11 to 12, Shipwreck will be open to the public, with an opening reception Friday, April 11, 5-7.

Shipwreck: UKAI Projects Exhibition at Milieux