As the world feels increasingly disembodied, I find myself increasingly preoccupied by materiality. So much of my work is immaterial: words are published online and lost as publications close, writing about books I never held or exhibitions I never stepped foot in. The latter is an admittedly immense challenge, but I still felt compelled by Oscillation, the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris’s outgoing exhibition.

Research-Creation

Maybe it’s because I’m always oscillating in my own way, between industries, mediums, genres, between my work, my art, and my research, and Oscillation is a love letter to research-creation. “For me, there’s no research without creation and no creation without research,” Milieux co-director Alice Jarry tells me, “when your research deals with material, it’s very hard to keep it abstract and just read papers for six months before doing anything. You have to mess around with material, and you have to experiment and try things to see what they produce, not only in your head but in the lab.”

Jarry was the co-curator of Oscillation, which featured about a dozen Milieux members and alumni.

It all started in 2021 as Jarry, Marie-Pierre Boucher, and Samuel Bianchini co-directed Membranes in Action, a research project examining membranes as both objects and interfaces between methods, disciplines, and people. As the research led them to biomembranes and biomaterials, Fossilation was born.

The exhibition’s central piece, Fossilation, is a large translucent bioplastic membrane that asks: How can we look at images from a sustainable perspective? Obsolete electronic devices, screens, cables, computers, are imprinted in the membrane, images fading into the material like fossils of our time, “Each part of the membrane was approached a little bit like a funeral,” Jarry explains.

Fossilation’s dual nature is revealed through its parasitic nature, attaching to the center’s infrastructures to capture and repurpose residual energies —heat waste, air conditioning, the vibrations of visitors— bringing “fossils” back to life through sound and vibration.

Artist-researcher and Milieux member Brice Ammar-Khodja found that traditional academic routes were insufficient for a practice “deeply connected to aesthetic and sensations,” wondering, “what would be the best way to create a kind of an archive or a documentation that’s not exactly a documentary, that’s not a paper, and that’s not just an art installation 100% aesthetic.”

This resulted in Ammar-Khodja’s doctoral project En, Sur, et Face (a play on words meaning ‘on, the, and surface’), an immersive installation which consists of eight tubes personifying encounters with site participants. Metallic residues collected from the contaminated soil of Montreal’s Le Champ des Possibles are activated by magnetic fields, dancing in response to the recorded voices of the participants playing through embedded speakers. Ammar-Khodja also collaborated on Recapture, a project that materializes atmospheric pollution, using abaca fibers and fans, using real-time air quality data to modulate its rhythm.

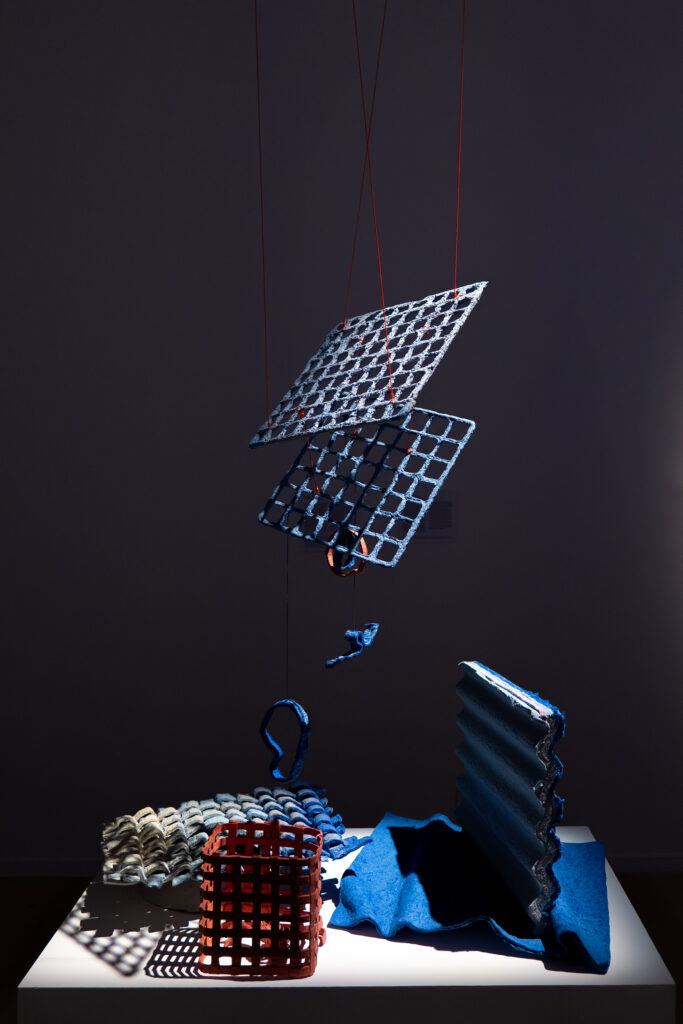

Textiles and Materiality member and designer Anne-Marie Laflamme conceived of research-creation as “a very iterative process where I gain knowledge from making, and although I try to have a plan, research through design or research-creation is really unexpected because as you gain knowledge it creates new branches of research.”

“When I worked with my pieces, I discovered a lot of tensions, like between smoothness and roughness, colourful shapes that attract us, but when we get closer, there’s also some type of repulsion because it’s, it’s rough, it’s unfinished, like there’s a sense of familiarity, but there’s also a sense of discomfort. So, I felt in my work this type of oscillation.”

Paris-Montreal

While Fossilation feels designed for the Canadian Cultural Centre’s art gallery, it was originally shown at the Centre Pompidou in February 2021 as part of the Matières d’Image exhibition. While the exhibition’s visibility was heavily impacted by Covid-19 restrictions, Fossilation was noticed by the Canadian Cultural Centre who invited the group to co-curate what would become Oscillation.

Ironically, given the subject matter, much of the set up for Oscillation had to be coordinated remotely, across the Atlantic. In fact, many of the featured works were developed and designed at Milieux. To navigate this distance, the team produced 3D models of the exhibition spaces and the artworks, allowing curators to choreograph a digital dialogue between the works before they were installed. This digital planning was crucial for the exhibition’s immersive components, which required adjustments and compromises to coexist seamlessly. Laflamme made small changes to simplify Remnants Archaeology, which was inspired by the mountains of scrap found in textile landfills.

For Ammar-Khodja, this meant presenting En, Sur, et Face without its olfactory element to preserve the exhibition’s harmony. Given the environmental themes present throughout Oscillation, bringing works to the Canadian Cultural Centre, located in the wealthy eighth arrondissement, presented an ethical challenge. Ammar-Khodja reflected, “What is it to talk about air quality when you’re actually transporting an artwork to a plane from one place to another?”

Material-Immaterial

Discarded technology, polluted air, residual energies—Oscillation challenges the perceived weightlessness of our digital age by making the invisible visible, whether tech giants, politicians, or consumers like it or not. There’s a confrontational edge to Oscillation.

Ammar-Khodja’s rematerialization of participatory experiments in En, Sur, et Face, evokes the unpleasant past of Les Champs des Possibles, a former marshalling yard and wasteland.

“ So now it looks green, but the soils are highly contaminated, and people are using it as if it were just a public garden, they have no idea about the contamination,” he explained.

“The whole idea is to kind of recreate the conditions of inquiry in the exhibition place. So, the public can navigate the piece and try to rebuild these moments that I’ve spent with the public, and the way their perception of the space evolved before the intervention and after.”

The movement between the seen and unseen extends to the gallery’s design, where signage was obscured through bioluminescent ink, hidden until activated by a system of UV lights.

“There’s a whole system in the exhibition that is a kind of dynamic system where sometimes you cannot see the text. Sometimes you can see it, so it’s all over the place within the exhibition, but it appears and disappears at different moments in time. Creating a dynamic back and forth between the space, the artwork, the text, the reflection, and the descriptions of the artwork was fundamental in the process,” Jarry explained.

Even from a distance, Oscillation’s scope is immense, serving as a vital reminder of what is only achievable through collaboration.

Across the ocean, video interviews, and photos on the cloud, Oscillation keeps us grounded. The works presented by these artists and designers invited visitors to change their perspective on their own environment. Whether it’s reconsidering the environmental impact of digital devices, giving a second life to food waste or looking anew at the composition of our soils, the exhibition constantly returns us to the materiality of things. Just as the exhibition illustrates tension between the intangible and the tangible, research-creation iterates endlessly between practice and theory. Oscillation doesn’t just showcase this process; it is this process; evolving between materiality and abstraction since its very conception.

– Nadia Trudel, Milieux Storyteller