By: Matthew Raymond, electro-acoustic musician and MA candidate in Philosophy at Concordia University. His research explores the history of metaphysics, temporality, and the contemporary resonances of ancient spiritual practice.

Martín Rodríguez is a multi-disciplinary artist and curator based in Montréal, Canada. His work draws connections between the intrinsic communications in sound to create experiences that engage in the present.

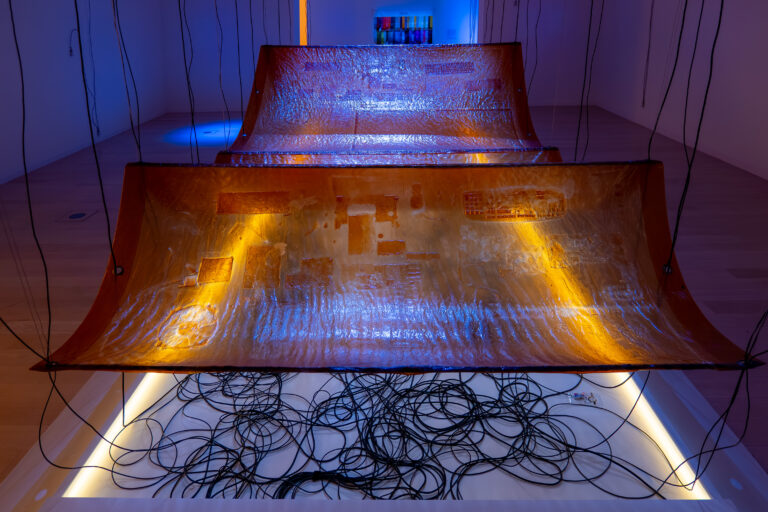

In this interview, Matthew discusses with Martín the impetus for In Search of Aztlan… an intervention-based work using dashcam videos and radio recordings made in 2019 as Rodríguez explored the area around his childhood home along the border between Mexico and the United States. Check out documentation of the project which he is presenting at ISEA 2020.

Matthew: What was the genesis of the project In Search of Aztlan?

Martín Rodríguez (USA/CA): This is a project I’ve been doing a lot of research for, and it’s rooted in my own history. I’m a Chicano, which means I’m half-American and half-Mexican. I grew up along the border of Mexico and Arizona near a city called Nogales. I’m actually from a smaller city named Rio Rico but Nogales was considered the big city, and we would go there quite often. This is a town that is split in the middle of the Mexican and American border. So when I was growing up, I was never American enough for the Americans and never Mexican enough for the Mexicans, so my identity was always split across this border. It has always been confusing for me. This project really began with the idea of going to the border and doing field recordings of radio signals that were crossing it and trying to use radio as a method to discuss what was happening along the border, not just politically but just culturally. Actually, especially not politically. I really wanted this project to exist outside of the political moment. I think a lot of people are quick to link it to the political moment that was happening during the 2016 american election, but it’s not the case. It goes deeper than that and the roots are before any talk of a border wall.

Last year I went down the border to start the research for this project, which basically consisted in building these handmade antennas, which were inspired by a folk craft from Mexico with roots to the pre-Hispannic era called an Ojo de Dios, which means “God’s eye”. Traditionally, they are woven for a child when they’re born and then every consecutive year a colour is added, associated with what happened to the child, and then it gets burnt when a child comes of age. My interest in the fact that the Ojo de Dios are said to be able to see the unseen, and so as a Radio artist, that intersected with the way we talk about signals. We can’t hear them, and antennas allow us to hear the unheard. So those two concepts connected really easily, and I came up with the idea of weaving antennas with magnetic wire along the thread in a traditional Ojo de Dios way. That’s the foundation of the project, the antenna building, and installing them as an intervention in itself.

M: Can you give a description of how it figures into ISEA?

MR: I brought a friend with me to document those preliminary research installations, and we were supposed to go back down and do it for real with a bigger antenna, you know everything bigger and better, but COVID happened so we weren’t able to do that. It really made me super depressed right at the beginning of all of this, because you know, like a lot of people, we had been investing years of thinking about and working on this. So I didn’t know where the project was going to go, to be totally honest, and I was trying to unwrap it and figure out a new direction, when I was asked by Erandy, ISEA’s artistic director, to participate in this mobile intervention thing. I had actually forgotten that I had footage that I took on one of my first trips, where I had a GoPro stuck on the dash of the car when we were driving around the desert, unveiling the scenery.

The project is called In Search of Aztlan… Aztlan is the mythical homeland of the Aztecs, which was forgotten when they left. It was this place populated by all this paradige imagery. In the 1960s and 70s, the Chicano movement really took that concept and made it their own because of what was going on in the United States at the time, they were being displaced, farmworkers weren’t being paid a fair wage. They were looking to take some sort of land, call something home because they existed in the cracks, and Aztlan became this concept that they applied to a mission statement of sorts. And so in putting the video together for ISEA, it actually ended up working really well because it was this abstract vision of the street, driving in the desert and sometimes in the streets of Nogales. Originally I just thought the project would somehow just exist in Arizona or on the border, because of the nature of the interventions, but now I’m really happy about being invited to do this, to the point where I’ll just try and find a truck next time it is presented because it works so well.

M: What drew you to radio as a medium? How does it play into the conceptual architecture of this project?

MR: It’s very personal. I had a brain tumor 7 years ago, and when it was removed, the left side of my body was paralyzed. It really challenged me creatively and artistically. In a moment of frustration, when I was playing guitar, I threw my guitar on the floor. When I did that, the radio got hooked into the pickups of the guitar and made the strings of the guitar kind of autotune the voices of the radio. That really inspired me to try and use radio as material to make music with. That was the impetus for radio entering into my practice. And since then, I can’t get enough because I find it so powerful, there are so many different ways we can interact with radio. It really sparked my creativity and my understanding not just of art, but also of society, and science and how the universe works. When you get into radio, radio art specifically, it gets pretty deep. Radio waves are all around us, they are a natural resource just like water and air, they are penetrating us at all times, right now, through you and me. We use radio signals to communicate, for WIFI, Texts, Cellular service. Some of our most advanced technology is based on radio communication, to this day, and it’s sometimes considered an old or outdated type of technology. That in itself is already inspiring as a material to work with. On top of that, asking what messages we are sending along those waves opens up a whole other box. Back in the day when Tesla and Marconi, the early radio pioneers, discovered radio, Tesla thought he was hearing spirits from the other side. It was really just weather he was hearing, picking up thunder or storms from faraway. I’ve always been someone who liked working with found material, found sounds, and radio is constantly inspirational and constantly opening new avenues for conceptual, creative, and aesthetic work. With this project, I wasn’t just picking up raw sounds that were there, but also songs that were being broadcast, and discussions that, in some ways are new, but in some ways have been going on for centuries. That part of North America has notoriously been a migration space. With the conversations and music, it’s not just noise, it allows us as spectators to connect with something we can understand.

M: I know you worked at Eastern Bloc for a number of years. What did you learn from that experience? What were some of the successes and challenges?

MR: At Eastern Bloc, I worked as the technical director, the lab director and the co-general director over four years basically. I started off as an intern, and from that followed this series of events where people left and I was able to step into positions. So I started as an intern for a radio thing they were doing at the Sight and Sound festival, and after that the technical director ended up leaving and I was asked to fill those shoes. I did that and then the lab director stepped down, and so I was asked to fill those shoes. And then Eliane, the artistic director, went on maternity leave, and I became the interim director. It was all these steps that led me to have to learn very quickly on the job. It was a hugely inspirational period of my life, and I learned so much while being there as both an artist and an organizer. That’s something that is still important to my practice, curating and doing events, because I love organizing and through my experience at Eastern Bloc I learned how to do it well. I think the biggest challenge was just making sure that there is a public that is coming in to see the works, and that there’s enough money to keep it running and keep paying artists fairly. I think that’s the biggest challenge for any not-for-profit organization or arts centre.

M: Tell me more about your event practice. What makes a really good workshop? What are some things that you view as being really essential?

MR: Ok, I’m really glad you asked this question because I’m very picky about workshops. Personally, I don’t like workshops where I’m just being talked at for hours on end, or when I’m just being crammed with information, so much so that when you come out you weren’t able to retain anything. I think those are the two big mistakes. For me, I prefer to provide less material, but really focus and give quality instruction. On foundational material. I also think a big thing in a good workshop is that people need to fail, but they need to fail in front of you so you can show them how to fix it, so that they can see that failure is part of the learning process. I think a lot of us have been programmed through the educational system that we shouldn’t be failing, and actually it’s exactly the opposite, that we should be failing and we should learn from those attempts at trying something out. In making those attempts, you are making links that are not correct, and that’s fine, because in making those mistakes you realize that instead of “point a to point b”, it’s actually “a to c” or “a to x”. Or you find your own route to getting there.

I have another workshop that I’m starting to give now which I call, “Roger Roger Do You Copy: Introduction to Radio Art”. This one is more about trying to arrive at an understanding of what radio art is, because there are a lot of questions about it and what it can be. It can really be so many different things. Basically what we do is a mix of reading some conceptual and philosophical texts around radio art, discussing them and me presenting some examples. It’s very open, very exploratory and I’ll have some transmitters there and show them types of works we can explore with radio, and go into the technical know-how of radio works. Sometimes we’ll talk about the power of a voice over the radio, and that’s super powerful because you have this voice coming to you that has no body to it, you are filling in those gaps and imagining what body is associated with the sound. I find that to be super powerful, and I find that becomes a very good way of opening discussions around sound and sound art.