ChatGPT happened, and suddenly AI made its way into many aspects of my life: It appeared in all sorts of Op-eds about the end of education as we know it, and my favorite podcasts dedicated episodes to it (I particularly recommend you to listen The Daily). It has also been a constant topic of conversation with friends over the past two months. Have you used it? Will we lose our jobs as programmers or animators? Have you asked it what it knows about yourself? Do you know you cannot speculate on crypto with it?

As the hype and concerns around chatGPT keep growing, especially as it relates to education, I have started to perceive how AI, or generative AI, has been used in the classroom. I am not a teacher or professor but a Ph.D. student who has spent a fair amount of time in a classroom. Here I present four guideposts that can help professors and educators use AI in their classrooms and have fun along the way.

Guidepost number one: Get your hands dirty.

Dr. Fenwick McKelvey, the course convener, told me he wanted the class to use AI rather than just talk about it. He spent the summer learning about critical making, especially from Ph.D. student Zeph Thibodeau, member of the Machine Agencies research group at Milieux. As they worked together, the concept of research-creation – a scholarly activity that considers art and making as a research method in its own right – finally clicked for him. Interested in research-creation possibilities to produce innovative scholarship and transform pedagogy, the course design shifted from a traditional seminar to a workshop format with team-based work.

Cognizant that he was new to the craft, McKelvey asked Zeph to co-teach the class, who agreed. Aside from reading and commenting on other people’s research (as he has traditionally done as a communications professor), they designed a course for students who were required to make a Twitter bot – a kind of artificial intelligence – for the Machine Agencies account.

The plan, much like ChatGPT, changed when Stable Diffusion launched in early September. Stable Diffusion is another kind of generative AI that collages images together based on prompts, much like how ChatGPT writes by predicting words based on its training data.

The class became a lodestone to today’s experiences with ChatGPT, where a technology arrives suddenly in the classroom. Research creation in class gradually integrated Stable Diffusion as the tool became easier to use.

Trying to showcase what a bot could look like for the class, Zeph and Fenwick began discussing how they could use Stable Diffusion. Fenwick does not recall how it happened. Either Zeph started talking about the book Greenworld, which imagined humans in the future, or Fenwick started talking about his childhood book Barlowe’s Guide to Extraterrestrials. They settled on asking Stable Diffusion to design animals living in Montreal after a 2-degree increase in global temperatures. Fenwick worried about the climate emergency and whether the AI did too. As it happened, the AI never really delivered, offering collages of images and strange animals, but never examples of actual thinking about what global warming would mean for Tiohtià:ke/Montréal’s residents.

The class had to do the same. Four teams, composed mainly of graduate students from the Communications Studies and Individualized Studies, presented the results of the projects that would lead them to develop their Twitter bots.

I could see the research-creation ethos manifesting itself in their presentations. For instance, one of the groups came up with a Twitter Bot that performs a ‘vibe check’ of the platform. The VibeBot extracts a large sample of public tweets corresponding to a trending hashtag and analyzes them as an assemblage using a sentiment analysis model to determine the hashtag’s vibe in one of six predetermined labels (sadness, joy, love, anger, fear, surprise). The label ascribed to the hashtag is then processed through a text-to-music AI model, which generates an audio file that represents the hashtag’s vibe. The VibeBot then produces a tweet composed of an audio file and its corresponding hashtag.

The bot has yet to be built. But the students clearly know the work pipeline and its challenges. They had to re-adjust their expectations as they moved along and created their proposal. They did a fair amount of research: from exploring “the state of Twitter,” as it was recently acquired by Elon Musk, to engaging with affect theory and senses literature. As McKelvey, they really appreciate the support they got from Zeph in figuring out what critical-making entails.

Guidepost number 2: Remember to play.

When talking to Fenwick about his initial experiment with Zeph, he told me that he really liked the results because they were experimenting, and were, for a brief moment, in a time where he had a chance to be creative. One of the things I enjoyed the most in the class I attended was the central role attributed to playing.

Two teams came up with an internet-based game to present their work. One of the teams called their project [Art]ificial Intelligence and used AI to generate art pieces based on existing ones. The game consisted in guessing, which was the non-AI generated element. It was challenging but also super fun. We all had to access the link to the game on our phones and vote. The winner was Fenwick, who claimed it had more to do with being closer to the screen (though his time playing around with images along with Zeph probably trained his eye). I could not get any answers correctly, but I eased up. Suddenly, I started taking notes less frantically and enjoyed being there.

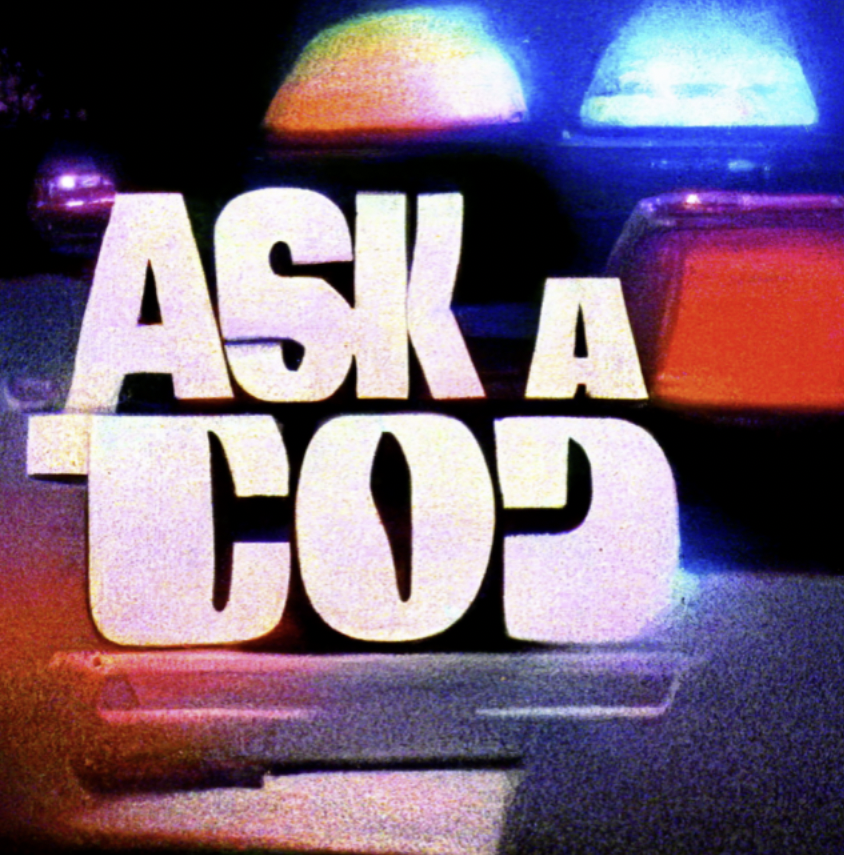

Another team came up with a game called “Ask a Cop.” It takes you to an imaginary setting where you try to understand what it is to be a police officer in Minnesota: “Welcome, everybody! It’s time for another round of the “Ask a Cop” series, where we answer your questions live about what it’s like being a cop in Minnesota!” As the game progressed, two imaginary police officers, Ali and Sammy, offered their answers to everyday law enforcement situations. As we played along, we could start perceiving how biased the data that feed those bots is (and I am sure more than one of us developed the inner need to do something about it).

Guidepost number 3: question AI.

This could sound too obvious for those trained in critical theory, but it is crucial to remember when critically approaching AI. As a good friend told me, and as I have been learning in the past few months: AI is all about the data you feed it with. So, what is the data feeding the AI bots students use to design their projects?

In the case of “Ask a Cop,” as the game progressed, we could see how the responses that Sammy and Ali’s got from the AI were determined by police actions that perpetuated police brutality.

Another group decided to take a new direction in their quest to question the AI. As journalism students, they were worried about automated journalism, so they decided to explore if AI-produced journalism perpetuates or negates the existing bias problems in the news industry. They designed a Twitter bot focused on GPT-3, what ChatGPT runs on, that could create automated headlines. Their purpose was not to ease their workload but to see how existing news headlines perpetuate racial and political bias in news reporting. They shared many dreadful reactions generated by some of the draconian headlines created with the prompts the group fed the GPT with (all coming from real local newspapers). Their experiment showed how important it is to pay attention to the ethical implications of automated journalism.

Guidepost number 4: Use AI for what matters to you

The selection of Minnesota as the city where Ali and Sammy operate is not casual. It has a symbolic meaning and political significance as the place where George Floyd was killed at the hand of policemen in 2020, and a wave of BLM protests expanded worldwide against racialized police brutality. It resonates even more as I write these words as we are grasping the death of Tyre Nichols in the hands of police officers in Memphis. I like this project not only because it shows the political and creative affordances of AI but because it was the one that spoke to me as a social change scholar. As it addressed a topic that I felt close to, it allowed me to see how humans and machines co-create each other’s realities and promote (political) actions.

All four presentations in this class and the two instructors’ experiments exemplify how action is not a preformed essence that resides within people or objects but something they “coproduce” together, as sociologist Bruno Latour argued. In this class, students and professors alike had the chance to use AI to explore topics close to their hearts and create bots that question and transform the things they don’t like.

In a moment when transactions between humans and machines are stronger than ever, this class showed me how AI provides a space in which students can manage their affective states, speak truth to power and create social change tools. So, why would you use AI to cheat on an exam when you can use it to fight police brutality, deconstruct news bias, create sensory experiences, and have a good laugh?

by Melina Campos Ortiz, PhD student in Social and Cultural Anthropology.