“I’m Agnus and I’m here to tell you a story.” With this, artists Sue Proctor and Luce Bernard begin a two-day exploration of performance and processual encounters for Milieux’s LePARC exhibition, Embodied Interventions. Showcasing the efforts of two weeks of student-led interdisciplinary experimentation in performance, Embodied Interventions brings artist academics together in thoughtful collaboration. The exhibition is organized by LePARC coordinator, Lucy Fandel, co-curators Margaret Lapp and Eija Loponen-Stephenson, with technical and organization support from Alastair Cavanagh.

Day One

The exhibition begins with Proctor and Bernard’s The Paper Crane. Dressed in vibrant oranges and loud patterns, Proctor brings us on a narrative journey rife with humor as her clown personae, Agnus. Bernard’s punctuated strummings provide a syncopated soundscape to which Proctor moves. The story follows a restauranteur whose business is affected by construction, but through the magical capacities of a paper crane bestowed upon the owner, people come, eat the soup, and occupy the space. Importantly, it is an embodied intervention that brings the bird and restaurant to life: clap three times and magic happens.

After the performance Proctor sits down to give voice to the practice of clowning as a social intervention. Throughout the talk, laughter is emphasized as a particularly transformative force, enabling us to understand things from a different perspective, one that doesn’t presume to take things so seriously. As Proctor notes, “the idea of making mistakes is fundamental to clowning.” Clowns challenge normative ways of being and doing, offering unexpected perspectives that produce laughter and facilitate joy. Speaking to this point, featured artist Emilie Morin tells Proctor that her “gestures kept making the world bigger.” Through action as intervention, Proctor’s movements expressed the themes of transformation central to The Paper Crane and clowning as practice.

Leading us between the performances and their various spaces is the ambulatory performance by Patricia Ragazzon, S. A. T. I. R. S.: Simple Actions to Inspire and Rupture Spaces. Ragazzon carries a conventional umbrella, draped in colour-rich, glittery fabrics, and adorned with streamers, postcards, and interior lights. Simple actions and ordinary materials make the hallways of Concordia feel different, no longer stoically academic but enlivened with processional joy. At different moments spectators and artists enter and exit the overhang of Ragazzon’s umbrella. Stepping inside you understand what she means by rupturing spaces, as the glow of the lights and sections of fabric encase you in a secondary space, even when inside the mundanity of the freight elevator.

Ragazzon accompanies us to the final space of the day for the concluding performance and artist presentation. Spectators take their seats before encountering the darkness of Concordia’s Black Box which quickly becomes enlightened by a directed studio light and video projection. The multimedia piece, Gee Gee Gee, Deodorant, and Say Yes When You Get Married by Heather Anderson, Brenan Dwyer, Peng Hsu, Chloë Lum, Laura Jeffery, and Sasha

Kleinplatz, is wonderfully hard to describe. Dancers begin swaying in front of a light like little sun-actuated flowers while a winding narrative spiels over loudspeaker and corresponding video slide projection. Through rapid narration we gather a story about armpits looking like sunflowers and armpits people paid to visit, a narrative about a mother and a child and dating apps. A looming figure sits with their feet propped up on a classroom desk. The dancers approach the desk and either kiss it gently or grab deodorant off it and apply it with vigor. Anderson writes that the piece “explores what it means to move (with) the grammar but not the words,” demonstrated in movements that are at times gentle, and other times rushed and sharp. Throughout I can’t stop smiling with intrigue and enjoyment and I’m sad when it ends. When I turn to the program for the showcase, I see in the piece’s description that “it has more, and we are still looking.” I’m still looking too.

Closing out the day is an artist presentation by Emile Morin on her co-created work Le spectre anime nos os with Ryan Clayton. Le spectre anime nos os is self-described as “a work of braided dance.” Weaving individual choreography recorded with motion capture technology, Morin and Clayton compose a virtual transmogrification of their movement practices. Rendered into a two-channel video animation, Morin and Claytons movements take shape as little bits of corporeality floating amongst conventional objects of experience; eyes, legs, and talon-like pigeon feet float amongst balloons, a recycling bin, and a cell tower. Morin notes that each of these things function iconographically, telling their own story. The recycling bin recalls a performance the duet did during the pandemic over skype, while the cell tower is representative of a nervous system. Through the virtual representation of embodied movement practice, Le spectre anime nos os works simultaneously as performance and documentation, challenging the normative conundrum of archiving process-based work.

Day Two

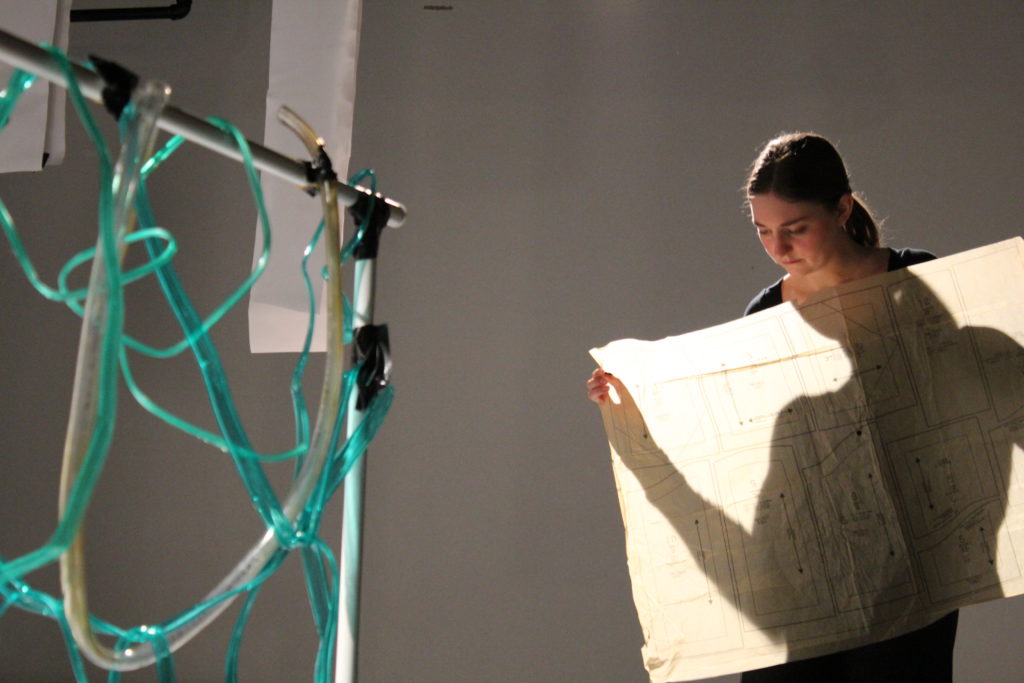

The second day of Embodied Interventions began, like the first, with a narrative introduction by Malika Pa.am and Hannah Schallert’s Mechanic Narrative. Composed of a multimedia installation and electronic soundscape, Schallert weaves her body amongst varied objects to probe at the boundaries of technology and ecology. Centering around a figure dubbed Mother_Board, Schallert navigates through bits of materiality, rolling up pieces of cotton-like stuffing, clipping notes to cardboard, and pouring water into royal blue tubing. This latter act is accompanied by pithy statements by Schallert who is “watering the Mother_Board” thus “giving life to the body”. At the end of the piece, spectators are asked to draw the shape of a secret, place it into an envelope, and walk it to Schallert, sitting amongst the performative debris to receive our geometrized intimacies.

Following Mechanic Narratives is Juan Miceli’s performative and multi-format video installation exploring machinic vision, Lecha Negra. Through dead technologies, in particular reels upon reels of VHS tape, Miceli interrogates how machines affect perspective, or as Miceli writes, “mold our way of seeing.” Arriving at the installation space, spectators are confronted with an amalgamation of objects while a video projection sits over the whole space like the beam of the moon. Reflecting one another, the objects mirror what the video depicts, and vice versa. At the center of the installation lies a mass of VHS tape, which after a moment of intentionally deceptive rest, starts to move around, mobilized by Miceli’s body. At moments the mass absorbs video tapes spectators pass into its free form composition, and eventually Miceli emerges to engage directly with the crowd, encouraging further interaction.

The penultimate performance is another interactive piece, Babushkas Lexicon of Gestures & Sounds. Conceptualized and performed by Anderson, Ragazzon and Marcela Szwarc, Babushkas Lexicon of Gestures & Sounds begins with the distribution of the eponymous lexicon; upon entry to the performance space spectators are handed a card marked with a single word. Words range from naturalistic nouns, like mountain and water, to verbs such as laughter. Spectators are meant to voice their words at random while the three performers stand under spotlight to provide the words movement. Words enact actions like an embodied instruction manual, causing the performers to move about in an unevenly distributed and occultist Simon Says. Someone shouts out “ghosts” and shushing erupts out of the trio in a cacophonous interplay. “Laughter” is said, and laughter ensues. As people shout words with varying speeds, actions are interrupted, and when the crowd withdraws direction, silence brings a performative reset, a moment of lull before the next word is spoken.

At the end of the performance, spectators are ushered back out into the hallway for the exhibition’s final stage reset. Entry back into the performance space is once again mediated by paper, but this time spectators are asked to fill out their personal karaoke requests for Tricia Enns’ and Miceli’s—also known as Tornado Trish and Hurricane Miceli, respectively—Competitive Karaoke Game Show. Thoughtful speculation ensues as everyone hums and haws over what song to sing, wondering what is within their vocal range, and what they might be willing to expose to others. No matter, upon entry into the space, teams are divided based on seating arrangement, and all song requests are denied. Tornado and Hurricane call one singer from each team, and a slew of background dancers and impose the battle cry upon them. Singing at the same time, teams duel in a game of “karaoke or die” belting out top hits like Dolly Parton’s “9 to 5” and L7’s “Shitlist.” As Enns and Miceli write, “Karaoke has never been so fierce.”

All of this is to say: what is an embodied intervention?

It can come in many forms: dancing, clowning, singing karaoke, covering oneself in VHS tape or even frantically and fictively applying deodorant. Shared amongst each performance and discussion was a joyful, funny hue. Gathered for two days, all of us embodied, all intervening into something or other, premised only on creating a communal aesthetic experience.

By Kristen Lewis, PhD Student Art History