“So, I too think sovereignty matters, and such mattering also engenders other ethnographic forms; in this case, one of refusal.”

Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus (2014)

Theresa “Isa” Arriola began her presentation with an expression of joy at having the unique opportunity of sharing her work beyond the frontiers of the academic space into the artistic venue centre daphne. As an Indigenous artist-run centre whose mission is to encourage a culture of peace and respectful exchange, the space embodies much of the values that animate Isa’s research. Her decision to sit in the audience made us gather organically around her, creating a more relaxed and amicable atmosphere. “Beyond the “Crossfire”: Refusing the Making of a Military Bombing Range in the Mariana Islands” – featured in the warm-up segment of In the Middle, a Chimera – unfolds from her lived experience growing up on the island of Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands, a territory profoundly marked by the pervasive colonialism and imperialism in the Pacific Ocean. Isa invited us to immerse ourselves in the reality of the naturalization of the militarization of the islands through the materiality of military imagery. Surrounded by two screens displaying bluish and fluorescent images, we were spurred to dialogically engage with Isa’s work. By giving these images new and evocative meanings, Isa gestures towards alternative futures for Indigenous peoples that privilege Indigenous sovereignty. At the heart of her ethnographic and creative practice there is the generative act of refusal.

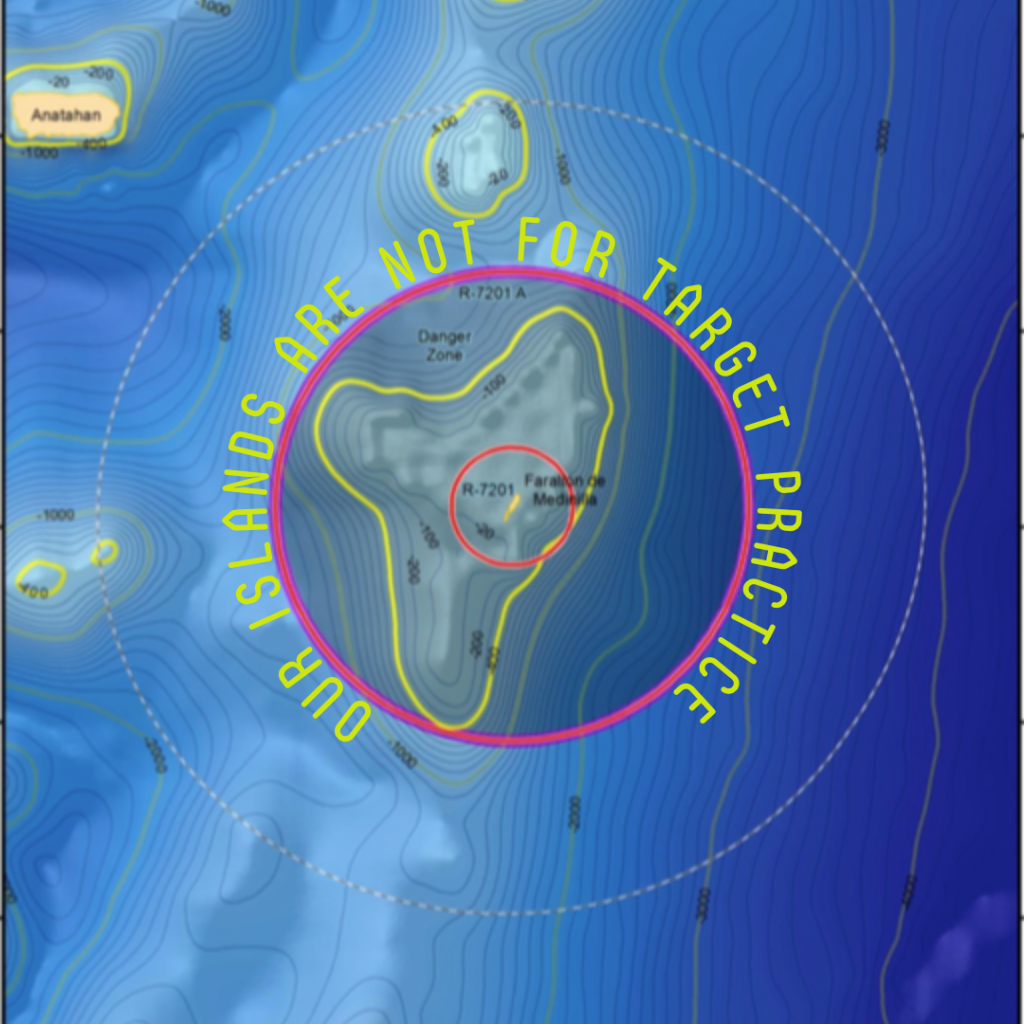

For the Indigenous people of the Northern Mariana Islands, the militarization of their territory is part of their everyday life. For decades, the US has been using their land/sea/air as territory for military training and testing as part of what they call The Mariana Islands Training and Testing Study Area. Happening mostly out-of-sight (underwater and far above ground), this type of militarization became naturalized. This reality, as Isa suggests, is sustained by a political narrative that erases the history and voices of Indigenous peoples in a multiplicity of ways. As a device that serves to (re)produce this dominant narrative, a stream of technical documents of environmental impact are continuously released by the US in terms of training and testing. These excessively long documents that are full of jargon and technical language – and surreal images of the military mapping of the region – render community engagement impossible. And that is precisely the point. They are part of a strategy of what Isa suggest, is a “weaponization of bureaucracy” to neutralize any serious participation in the decision-making process on the issues that impact the community. Even if there are participatory mechanisms in place, they are symbolic. Isa shares how she was inspired to undertake this research project in the first place in response to the acute powerlessness that she felt when participating in one of the public forums held by the government. To counter this dominant narrative, she resorts to creativity. By recurring to other forms of telling ethnographic stories, Isa provides a way out of this stifling colonialist strategy to silence Indigenous peoples.

Through a relational engagement with the visual military mapping of the territory, Isa enacts a kind of refusal that is generative. She refuses to simply accept the militarization of the islands as a given reality and to yield to the ongoing narratives of settlement that “foreclose the possibility of re-imagining these spaces as anything more than that”. She refuses to continue to be caught into the logic of imperialist states and colonial power. Her work proposes to re-articulate the terms of the conversation in view of envisioning potential futures where Indigenous sovereignty is no longer undermined by the vagaries of military objectives. Isa challenges us to imagine potential futures for her territory and her people and more broadly to (re)imagine collectively other ways of living together. Her appeal to refusal as a generative and future-oriented approach takes me back to Audra Simpson’s ‘ethnography of refusal’ as a quintessential example of her work. Saving the contextual differences, both authors engage in a form of anthropological work that is grounded in a political and ethical stance that puts Indigenous sovereignty in the centre of any present and future endeavor. One of the things Isa that commented about her own journey from Saipan to Montreal is precisely how the seemingly randomness of her movement from one place to the other is connected by the “flow of militarization across territories” and the “kind of struggles of Indigenous people who find themselves constantly negotiating their sovereignty”.

As the large front window of the centre revealed the greyish landscape of a rainy day of spring, we were surrounded by tropical images and the ocean blue and vivid greens. The aesthetics of Isa’s pieces incarnate such a kind of contrast as they convey “the utter beauty and the utter violence going together,” as Stephanie Creaghan so pointedly remarked during the round of questions. These images that seem to be taken straight out of a video game are embedded in a narrative that dehumanizes Indigenous peoples and turns their territory into a destroyable space. As an anthropologist, having the opportunity to learn how Isa resorted to creativity and imagination to respond to this situation has been truly inspirational. From the re-appropriation of the appropriator, Isa produces a unique kind of anthropological and artistic work. The resulting pieces do not give us closure, they are porous and open, inviting the audience to engage in a critical dialogue. She described her pieces as simple gestures of refusal. Perhaps, it is precisely this simplicity and openness of her anthropological work what makes it so powerful. As we were near the end of the talk, one ray of sunlight broke through the cloudy sky right behind Isa and some of us exchanged glances – as if we were all aware of the meaning behind that fleeting moment.