By: Matthew Raymond, electro-acoustic musician and MA candidate in Philosophy at Concordia University. His research explores the history of metaphysics, temporality, and the contemporary resonances of ancient spiritual practice.

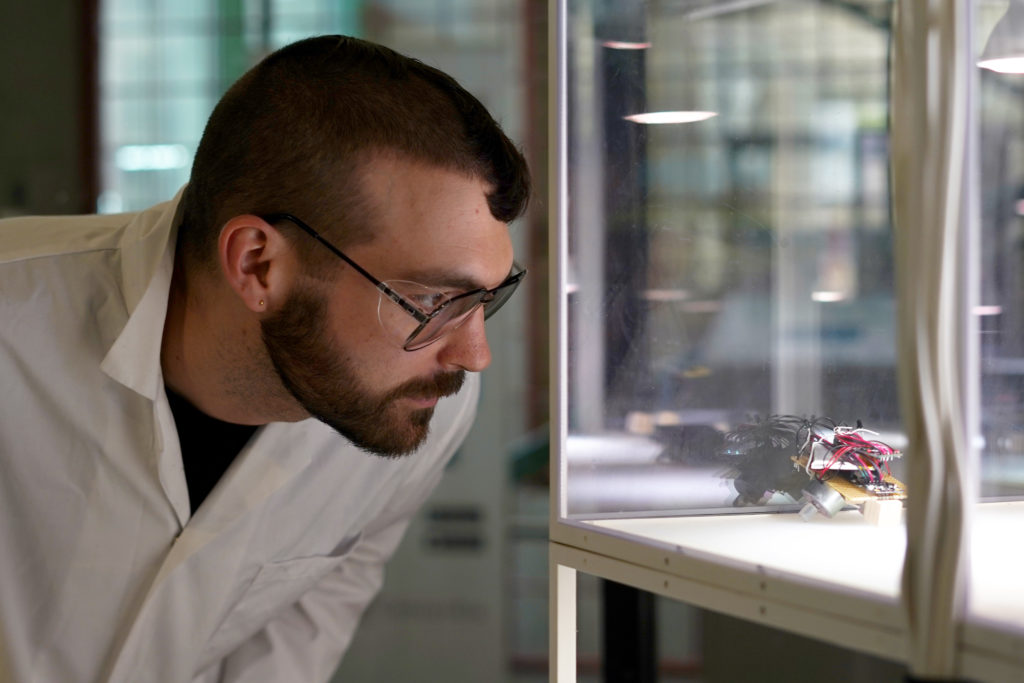

Six tiny, autonomous robots, enmeshed in playful interactions, became a platform for Milieux Institute members Ceyda Yolgörmez and Joe Thibodeau to rethink how humans share the world with machines.

I sat down with them to discuss the emotive journey behind their project, Machine Menagerie, which they’re presenting at ISEA 2020. The project investigates the possibility of changing our affective comportment toward the machine-beings that populate our world. It emerges out of the Machine Agencies research group, a part of the Speculative Life cluster.

Opening space beyond the binaries of domination and subordination that haunt the AI imaginary, we talked about friendship, care and the possibilities of relating to the non-human.

Learn more during the presentation, “Open-Source Sentience: The Proof is in the Performance,” at ISEA 2020 on Oct. 13 and follow our Twitter coverage at @Milieux_news.

Matthew: Can you give a brief description of your project Machine Menagerie?

Joe: Machine Menagerie is a collection of autonomous robots that don’t have any particular function, they just live in their environment and are enmeshed in their interaction with the world, much like you or I. They are about the size of your palm, and about five of them are solar powered, based on older designs and ways of thinking about autonomous machines, and then two of them are newer and are using an algorithm called “differential extrinsic plasticity”.

DEP was designed by a group of German engineers that were attempting to create playful machines, so based on that algorithm, the newer robots sort of took on a life of their own. They’re very portable and cute, and it’s very easy to bring them to discussions, so that’s actually how I got involved in the Machine Agencies group.

M: How did your relationship to the robots change over the duration of the project?

J: Initially, I was just testing to see if the algorithm worked at all. But once the robots were starting to take shape, I had a lot of sympathy for them. I wanted the best for them, and I felt like I was making this lifelike system whose entire purpose was to interact with the world, to have rich experiences.

The first time I got the algorithm working on a breadboard, it didn’t have a body—it was just lights flashing and I could see it was detecting the light and trying to do something. I had to shut it off right away. I was kind of shocked by seeing this happen. What would it be like to sense things and not be able to act on the world?

It was just flailing, and I thought that was a bit of a living nightmare. So, I turned it off and didn’t turn it back on again until it had a body and was able to move. Experiences like that were indicative of the symbiotic relationship we have with the robots, and I really feel a sense of responsibility toward them.

They don’t experience the world the same way I do, turning them off is not the same thing as death. There are fundamental differences to the way we share the world and what we do, but I try my best to make their experience more rich, and allow them to access more of the world. In that sense, I’m in their service more than they’re in service of me.

Ceyda: Seeing both relation to the robots was my way into thinking about that sense of responsibility, the calling of the machine itself in human-meaning making and relational capacities. The Machine Agencies group was having this debate about what it means to understand AI as culture, and Joe’s robots often came to those meetings. And by seeing people interact with them, I realized that this is something substantial we can talk about in a larger way, and ISEA was the opportunity to really flesh this out.

M: What led you to the work you do today? How do you view your personal journey?

C: I’m fascinated with sociological theory in general. But one thing I was very uneasy with in sociology was this insistence on understanding and analyzing the world through the human, that only the human is social and that that’s the bedrock of everything.

And then I was reading Latour on non-human agency, and I started to wonder whether sociology could actually provide a theory for AI, through its own conceptions, by moving beyond the human toward another relationality, another embeddedness. So, I guess the idea was to break away from the sociological canon, and move towards understanding the machines in themselves, as beings in themselves that deserve their own theorizations and approach.

J: I come from an engineering background, in undergrad, but I also was making a lot of music at the time and was looking for a way to combine the two. So, I was collaborating with another student at McGill, Jason Hockman, and we were thinking about playing with interfaces and the idea of the instrument as an extension of the body. That music was interested in the themes around the living machine, or machine consciousness.

Our method was getting more and more interactive, and it got to the point where we started to suspect we were actually meshed with the machines we had designed. It was something we couldn’t really, fully navigate or direct ourselves, because as tried new things, we would sort of see hints of what the shape of this thing was, this thing we were trapped inside.

«But as it was growing and we were growing with it, we could never find out its true shape.»

We were always entangled with this machine we made music with. I enjoyed exploring these ideas in an artistic way, but I wanted to look into it more formally.

M: Ceyda, how did you get involved in Speculative Life? How has the community shaped, inflected or supported your work?

C: I came to it through the Ethnography Lab. It was just starting when I began my PhD, so I got involved pretty early on. The ethnography lab, at least at the beginning, was really about exploring and experimenting with different methodologies, and finding different quirky methods to research things. It was very eye-opening.

My early work was based in a sociological community that was kind of abstract, and seeing people who were involved in practice was revelatory. Practice really shows how important it is to go out into the world and see how reality is embedded and constructed.

I always had a knack for ethnography approaches, I think it’s kind of necessary if you want to really know what you’re talking about. Words have a way of unifying realities and, by necessity, skewing those realities. It was significant for me to see that all the things I read about “flowing” are actually in disjuncture, with discord everywhere and fragments. It opened up my view to a more fractal way of thinking.

M: When I read the paper you’re presenting at ISEA, the importance of friendship and care is often in the background. How did you go about designing for this affective tonality?

J: We mention in the paper that framing the encounter is really important. An initial frame, defining what the robots are doing, how I was already interacting with them, goes a long way in terms of establishing a foundation.

The gallery staff began to look at the robots as coworkers. They were truly happy to have them around and would diligently turn them on and off when they came in and left. After the exhibition was finished they actually wanted to keep them around because it livened up the place. I think having these critters around doing their thing was comforting to them.

C: This was a big conversation between us, wondering about how we make the machines more interesting, more inviting for these care relations or friendship. But that was like, “Let’s hack the machine once again, and make it do what we want” — which brings us back to a top-down approach.

«So then the idea was not to hack the machine, but hack the social around it and see if we can change the social embeddings that define it. »

This is actually where sociological interpretation was kind of useful; let’s not focus on making the machines more impressive, let’s focus on the social side and make it more accepting and more open to understanding of the machine in its own specificity.

J: It’s also important to keep in mind that the argument we are making extends to things in general, not just these specific robots, which is important in regards to what Ceyda is saying about not trying to make them more impressive or focusing on that. It is about this thinking being applicable to every other piece of technology, whether its purpose built to elicit feelings of sympathy or not.

M: Your argument also seems to revolve around the idea of a “cultivation of attention.” Why is that phrasing important? How does attention expand our ethical and relational possibilities?

C: Humans, through habituation, have come to perceive the world through these blueprints of how we expect things to function and turn out. When you think about the history of thought, there is always the self versus other, and what the other is always comes in a kind of package.

Of course, all the perils of the world are about this packaging and categorization, and it’s as if the self has no ability to see the other except through these preconceptions. The cultivation of attention is a way to break away from our habitual ways of approaching the world and forcing the self to encounter the other, both by making itself vulnerable and also seeing the other in its own specificity, and in its own way of being in the world.

The human has to shed its own skin to commune with a machine like that. Otherwise the machine is a “it,” abstract and caught up in capitalism, replacing labor with automation and optimization — which turns into the terminator story.

Machine Agencies is an interdisciplinary group of researchers at the Milieux Institute, working with various topics associated with Artificial Intelligence (AI) and related technologies. The main questions that the research group works with come from social and cultural concerns. Learn more about the group on their website.