What happens if we abandon the clear and orderly expectations of how and what we should learn, and instead embrace the potential of messiness, collaboration, and the unconventional? How do experiential approaches to learning upend the conventional, and to what end?

A traditional seminar assumes what pedagogical theorist Paulo Friere calls the banking model of education, in which students receive knowledge deposits from the bank of the instructor. The blueprint of this model is what we think of as a “typical” classroom, featuring a spatial arrangement of desks facing a podium, or, at its most collaborative, a roundtable. Consequently, this layout structures the learning process, organizing it around the professor’s theoretical expertise.

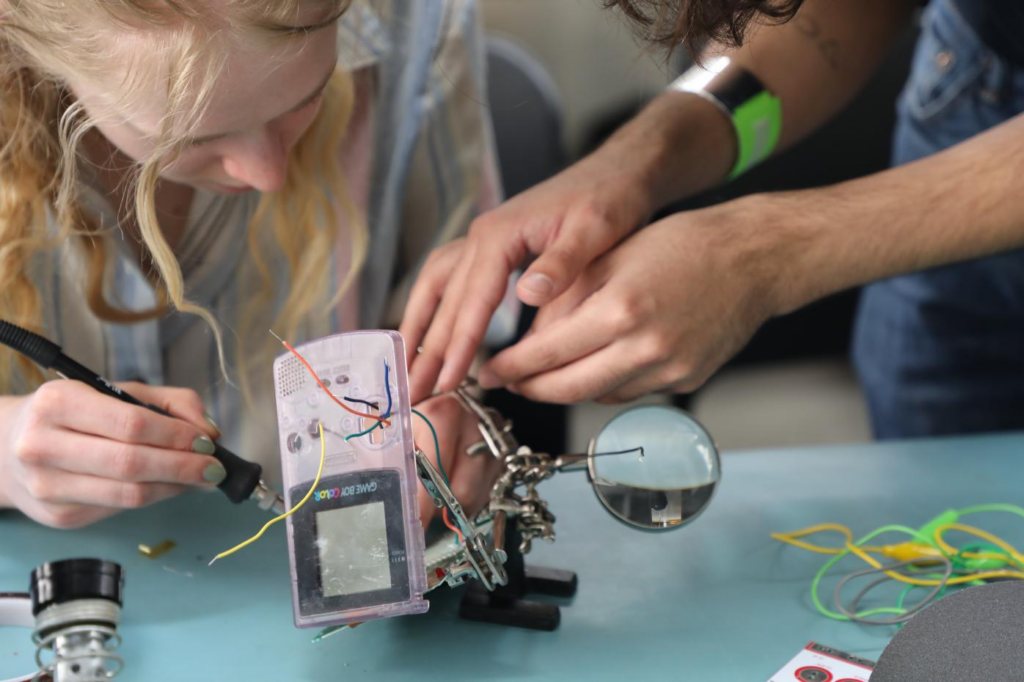

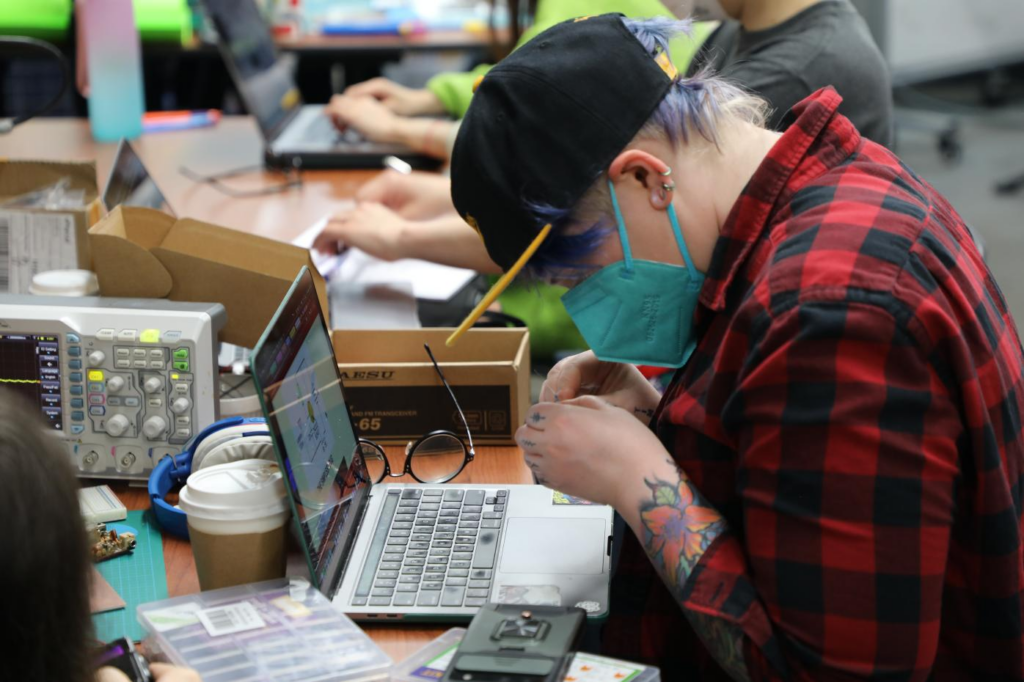

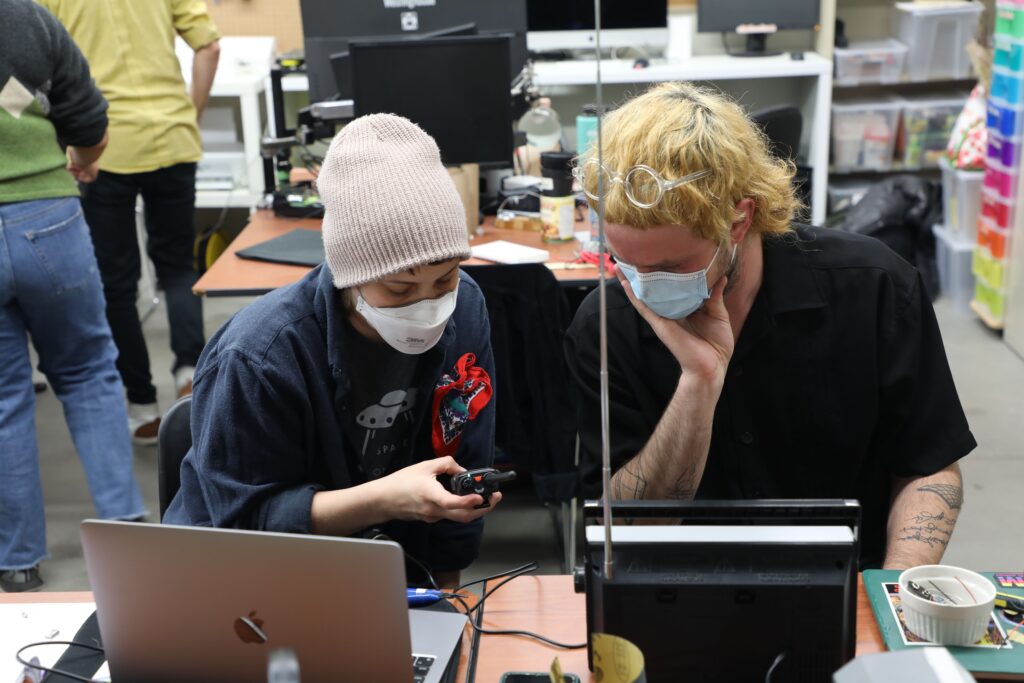

Milieux’s Summer Institute course, Mess and Method, operates on entirely different principles, with faculty and the teaching team hunched over soldering stations, scrounging the halls of the university for spare parts, debating in the hallways and conferring with experts over Zoom, as the needs arise. Designed and delivered by Concordia’s Darren Wershler and guest faculty Lori Emerson from the University of Boulder Colorado, the course embraces the mess of hands-on collaborative learning.

By taking a material approach to culture, Mess and Method reckons with the complications and incommensurabilities that come along with working directly with the “stuff” of everyday experience. Guest lecturer and information scientist Steven Jackson’s “Rethinking Repair” was a key text for the course that explores what Jackson calls “broken world methodology.” Broken world methodology moves away from abstract solution-oriented approaches to learning and engaging with material culture, asking “what happens when we take erosion, breakdown, and decay, rather than novelty, growth, and progress, as our starting points in thinking through the nature, use, and effects of information technology and new media” (221)?

The course consisted of one week of virtual instruction over zoom that emphasized theory and conversation, followed by a second week of in-person hands-on learning that allowed us to explore how theory fits with our practical experience, and where it may require reconsideration. Through concepts like maintenance, repair, and sustainability, discussions emerged in the first week about practices of care, ecological justice, and how to take a materialist perspective on relationality and affect. These discussions took practical shape at the beginning of the second week, when the class, instructors, and support staff all piled into the Milieux Makerspace. A collaborative DIY “third space” dense with tools for creation and tinkering, the Makerspace is lined with workbenches sporting familiar wares like screwdrivers, Allen keys, and wrenches, to the more specialized and esoteric tools like a Cricut vinyl cutter and a range of 3D printers.

Sitting on the central worktables of the Makerspace are four soldering stations. After initial remarks, we each turned to a station to build our own Blinky Robot: a tiny battery-powered device that, after a little soldering, powers two lights for eyes, providing the eponymous blink. Requiring minimal expertise, and easy to instruct for soldering novices, the Blinky Robot was the perfect ice breaker. Despite coming from different departments and research practices, this first assignment provided students with an accessible introduction to the skill-building and practical approach that would define the rest of the course.

Riding the high of successful creation, we broke into groups to dive into a week-long project of our choosing, from Solar Gameboy and console modding, to radio building and mimeograph repairing. I chose to work on repairing the old 1950s Gestetner mimeograph, which I did with my colleagues Yutong Lin and Yannick Desranleau. Prior to this course, I had no expertise in printmaking, having only tried lino-cutting a few times, and in no way knew how to repair a machine of really any kind. Throughout the week, we spent hours researching old manuals, de-gunking the clogged ink arteries of the Gestetner, attempting to get the old thing to work. This methodical cleaning and care led to an intimate acquaintance with the machine’s parts. I now feel familiar with the cranks of the Gestetner and know that the kind of paper used in the 1950s was rougher than standard printer paper. The feeding mechanism wouldn’t grip onto new paper, requiring us to improvise with the kids’ craft favourite: construction paper — a funny substitute for a machine intended make quick work of creating office-wide memos.

Throughout the week we spent more time immersed in the time-consuming tediousness of reparative labour than with celebrating successful printmaking. Hours of our repair time turned out to be cleaning time. This experience illuminated the underlying care work that goes into not just the production but the maintenance of any device, emphasizing the amount of technical and maintenance knowledge people need to simply keep things running. It also exposed the iterative and collaborative process of practical (and indeed, theoretical) learning.

Contrary to the bank view of teaching, in the mess of the real work of repair, learning becomes an ongoing and emergent process that engages the collaborative insights of whoever is around to help. Darren, Lori, libi striegl of the Media Archeology Lab, the course research assistants Alex Custodio, Lee Wilkins, Michael Iantorono, and Mario Gaudio, the print department technician, the folks at the woodshop and metal shop, and many more people played essential roles in helping us figure out how to get different pieces of the Gestetner to work. Prior to even entering the space, the theoretical expertise of those we read, and the various guest lecturers from Steven Jackson, Rutgers University Professor of English and Director of the Digital Studies Center Jim Brown, and Right-to-Repair’s Phil Reilly also informed our approach to repair and maintenance.

At the end of my PhD coursework, and after completing two degrees with predominantly lecture-based courses, Mess and Method challenged the presupposition that the transfer of information is sufficient for education. While the merits of lecture-based learning are significant, alternative spatial and practical orientations allow for novel insights, expanding learning beyond its well-established parameters. In many ways, the demands of the 21st century seem to require new approaches to learning that exceed solely the transfer of information. Working environments and work itself have become increasingly dynamic, calling for a more adaptive approach to learning that prepares one not only to learn, but to continually relearn according to the demands of the present. Higher education institutions like Concordia have changed to reflect the shifting terrain of contemporary life within our current techno present with Milieux Institute embodying this alternative pedagogical ethos.

Created with the intent of providing an expanded pedagogy for graduate education, the cultural and material infrastructure of Milieux encapsulates the shift towards experiential learning. By gathering students and researchers in Milieux’s spaces for a course length exploration, the Summer Institute enables a unique deep dive into Milieux’s extensive interdisciplinary offerings that not only introduces new researchers to the Institute, but also forms a community of practice. By offering courses like Mess and Method, Milieux affords the invaluable opportunity of engaging with material culture directly and collaboratively, unveiling what one can learn from differential circumstances and from the unconventional gathering of a mess of machines and scholars.

By Kristen Lewis, PhD student in Art History at Concordia University