A reflection of the event ‘Solarities: Thinking with the Sun’ | By Melina Campos Ortiz

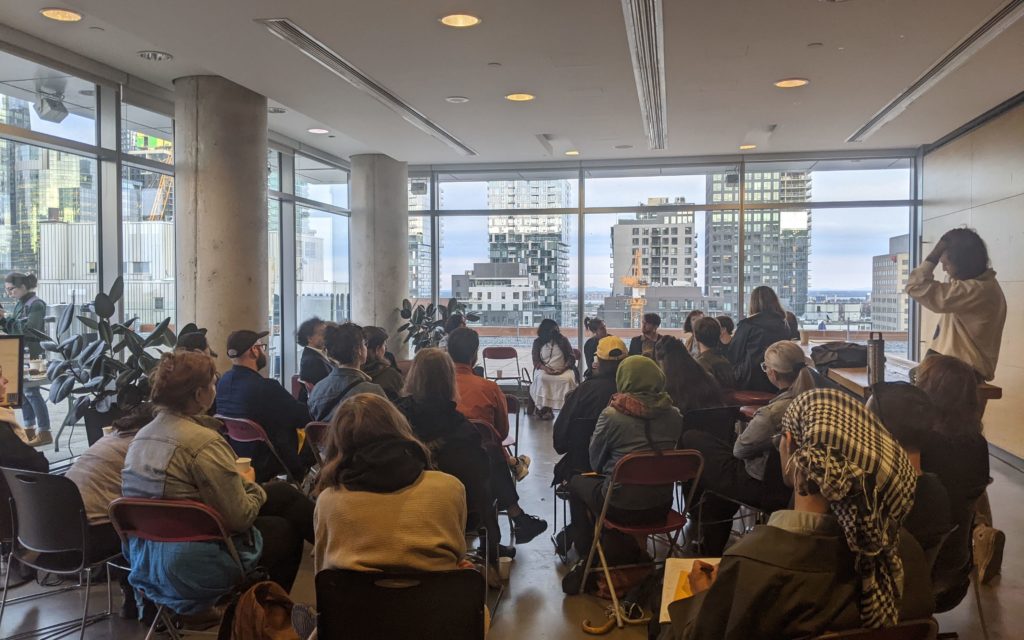

The Solar Media Collective at Milieux and the After Oil Collective, a subgroup of the University of Alberta’s Petrocultures Research Group, recently gathered a group of students, activists, artists, makers and academics “to think with the sun.” On September 21, the day before the 2022 fall equinox, we were sitting on Milieux Institute‘s windy terrace, looking forward to imagining alternative energy futures. The collectives challenged us to visualize: what might a world look like if our societies, communications technologies, and economies were organized around energy from the sun rather than from fossil fuels? And ask ourselves: What new infrastructures, institutions, and power structures would such a transition require? What forms of creativity, collectivity, and social organizing might we need?

Before the conversations started, the Solar Media Collective invited us to play a game fully powered by solar energy. To access the game, we had to follow a URL on our phones that would take us to Miliuex’s solar-powered server, displayed on the terrace. Such a server was built by the collective to host collaboratively developed art, games, and other material. In preparation for the event, the collective parked the server in front of Concordia’s Hall building for two hours and invited students to interact with it. They aimed at asking passersby to reimagine energy and communications infrastructure for a low-carbon world.

As we gathered, the presenters, who were as diverse as the participants and comprised communications, anthropology, art history and music students, professors and practitioners from Concordia and McGill, invited us to pick a copy of Solarities: Seeking Energy Justice. A publication better known as “the little yellow book” whose paper copies were available to the attendants.

To start the group off, one of the editors, Ayesha Vemuri, took us to the “little yellow book” epigraph, which summarizes its ethos:

Solarity (sō′lərĭ-tē): n. a state, condition, or quality developed in relation to the sun, or to energy derived from the sun (n.p).

According to her and her co-editor Darin Barney, the book considers the possibilities of organizing societies and economies around solar energy and the challenges of a just and equitable transition away from fossil fuels. They explained that far from presenting solarity as a utopian solution to the climate crisis, the book critically examines the ambiguous potentials of solarities which are plural, situated, and often contradictory.

While much can be said — and was said — about solarities’ pluralities and situatedness, the discussion focused on its contradictions. Which by no means prevented the group from engaging with its hopefulness. On the contrary, in the group, it appears to me was a tacit acknowledgement that “there is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns,” as Octavia Butler put it, and Jessie Beier could not resist reminding us.

This occasion was an initiation to take Butler’s new suns seriously. As feminist scholar and activist Ruha Benjamin suggests: “Butler’s prophetic words direct us to look at reality squarely and then propels us to find a round room to craft alternative realities” (2017, p. 2017, original emphasis). That day, we seem to have inhabited such a round room. The conversation at the Milieux’s windy terrace was soon replaced by the coziness of a group sitting inside, hot beverages and pastries in hand. Proximity that proved to be generative for collective meaning-making.

Through their selection of passages from the “little yellow book,” the presenters show us how they were thinking with the sun. Drawing from Natasha Myers’s work with plants, Robert Marinov encouraged us to engage with the sun’s relationality and generosity (see p. 27). Along with feminist physicist Lorenz Mayer, Hanine El Mir encouraged us to reimagine how solar solutions can trigger feminist imaginations of community participation and care (see p. 38). Isabelle Boucher reminded us that the transition to solarity must be approached as a matter of environmental justice (see p. 46). Drawing from her experience, she asked us to challenge neoliberal energy temporalities.

The discussion took several directions as we listened to the presentation and book excerpts that critically engaged with solar temporalities, decolonial and feminist solarities, solar punk projects and solarity as solidarity. But, perhaps not surprisingly, it generated more questions than answers.

In no order of discussions, these were some of the contradictions that we explored: Can we move past hyper-local renewable energy utopias? Is it morally acceptable to talk about moving past hyperconnected lives in the Global North when there are people in the Global South advocating against energy poverty? How can we fight the sense of urgency but embrace collapse as a hopeful method? How can we challenge the green growth grammar while benefiting from its affordances? How can we avoid romanticizing slow temporalities while acknowledging that the neoliberal pace is not sustainable? How can we embrace the no feasibility of what we do now but do it nonetheless because it can take us somewhere?

More than offering solutions or agreeing with what was said (I pointed out on more than one occasion the global north-ness of the analysis), this group engaged in an exceptionally productive speculative exercise. So far, I cannot say where it took us or where it can take us. And that is completely fine. As Donna Haraway reminds us, speculation is a deliberate and cultivated practice that we know little about how to do, and we do not know if anything will come out of it. But it will eventually affect each other’s imaginations (Haraway in Haraway et al., 2015).

What I can say for sure is that that day more than talking about solar servers, localized utopias or degrowth, we affected each other’s imaginations by inhabiting solarity as a condition. As the authors put it:

Solarity is the condition we inhabit as we struggle to make worlds and build futures out of the ruins of petrocapitalism. It inspires hope, creativity, and joy, even as it carries the weight of our guilt, shame, and anger at what we—or, more precisely, some of us—have been and done (p. 1, emphasis mine).

And we did so, not only because we did not shy away from solarities contradictions, but because sitting together in a sunlit space, we performed solarity’s relationality. We inhabited Ruha Benjamin’s round room. We explore Butler’s new suns. In the best Harawayian fashion, this was an event “to stay with the trouble”.

References:

Benjamin, Ruha. 2017. “But … There Are New Suns!” Palimpsest: A Journal on Women, Gender, and the Black International 6 (1): 103–5.

Haraway, Donna. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. London and Durham: Duke University Press.

Haraway, Donna, Noboru Ishikawa, Scott F. Gilbert, Kenneth Olwig, Anna L. Tsing, and Nils Bubandt. 2016. “Anthropologists Are Talking – About the Anthropocene.” Ethnos 81 (3): 535–64.

Vemuri, Ayesha, and Darin Barney, eds. 2022. Solarities: Seeking Energy Justice. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.