we move, just shifting by Brandon Brookbank was on view at the Centre CLARK in Montreal from January 15th to February 12, 2022. You can read the exhibition text by Lucas Regazzi and more on the show here.

When I was going through my first breakup, I remember constantly looking for anchors. Floating in a cloud of melodrama and marijuana, I felt untethered and disconnected from the world; I grasped at straws for tokens that reminded me of the indisputable fact of material reality. Crucifix chains, random trinkets, and unsewn shirt buttons filled this role for a while, but never quite satisfactorily, until the day I got an americano from Van Houtte. The coffee itself was ok, but with it came a small plastic stick to cover the opening on the lid. I put it in my pocket and played with it for the rest of the day, tracing its contours with my fingertips and convincing myself that this object – whose name I later learned is “beverage plug” – had been sent specifically to keep me company. I continued holding and playing with it on my gloomy, Wertherian walks. Soon enough, the forces of habit and proximity imbued the innocuous plastic stick with an aesthetic significance that transcended its humble utilitarian beginnings.

Walking into Centre Clark for Brandon Brookbank’s we move, just shifting, I was reminded of how porous the boundary between image and object can be, of how easy it is to turn items into cyphers and images into talismans. The solo show is the culmination of the artist’s MFA thesis in Photography at Concordia University, and it explores themes of intimacy, touch, and materiality through poetry, sculpture and photography. The show’s name comes from a couple of photographs – we move and just shifting – depicting a drinking glass with yogurt stains on it. Blurry hands and feet obstruct our view in a play of foreground and background that muddles the borders of each object and creates an image that is both flat and deep, eliciting a sense of profound proximity between the subjects and objects in the frame. The imprint of a finger lingers on the surface of the glass, like an unwanted memory loitering in one’s brain. The artist is exploring the affective and haptic charges of intimacy, which becomes evident in other photographs that bear the trace of intimate familiarity. In another picture titled Island, the artist materializes the immaterial flows of affection of their relationship in the form of lotion on their partner’s back, subtly telling a story of care, love and touch between two subjects. Through Brookbank’s lens, the mundanity associated with the still life is transformed into an erotics of the everyday.

While some photographs hint at intimacy, other pieces take a more striking approach. The first thing one notices in the room is the colossal fabric rope hanging off the ceiling, knock, knock, squeeze. Old white t-shirts with yellows stains and worn black t-shirts fading into greys are tied to one another with a doorknob at the bottom that keeps the rope tightly bound. In an artist talk, Brookbank explained that he used old t-shirts from their partner, friends, and themselves to build “a twisting pole to be tethered in the space to bring back the idea of connection in the grander sense.” Brookbank’s suggestion of connection as a macro phenomenon raises exciting questions about intimacy and community: how can we expand the closeness of interpersonal relations to a societal level? The sweat stains on the textile evoke the particularity of the artist’s relationships, as every friend is memorialized through their fluids, scents, and probably even tastes, but his sculptural work also conjures the marks that intimacy leaves behind. Brookbank tries to create a map of their closeness, and he ends up building a poetic language of intimacy itself, one that is relatable enough for anyone bearing the stains and scars that connection leaves on the material world, bodies and brains.

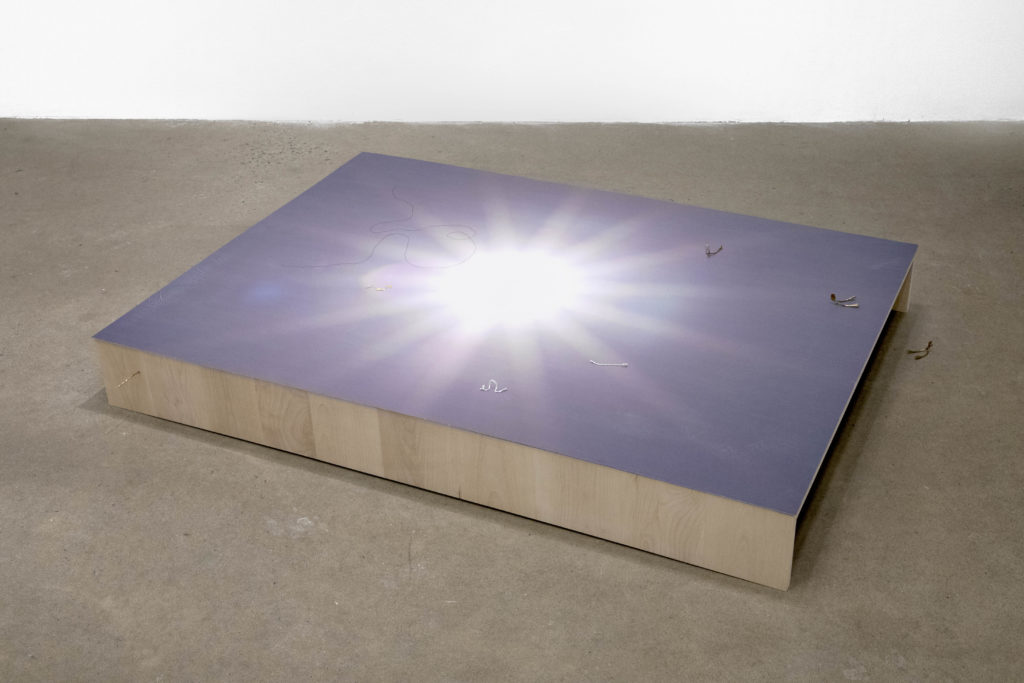

we move, just shifting features other fascinating pieces like A Room, a photograph of the sun that lies on the floor, as if mirroring the sky; Their Lurid Glow, another t-shirt sculpture with bobby pins on top; and Sorry, heels, an archival inkjet print depicting a blood-stained oversized circular glass with a sock hanging off of it. Most of the works in the exhibition play with layers of pictorial and material intervention. In very, very, very much, for example, Brookbank places twist ties on their partner’s neck which then suddenly materialize in the exhibition space, atop other photographs. Everyday waste and consumed consumables take on a new life, like the plastic stick that saved my life, as they anchor the viewer and artist to the certainty of material reality while connecting us to the affective memories that circulate therein. Yet, the objects in we move, just shifting not only communicate, they also intrude. The photographs in the show are often obstructed by lines, scratches, blurry feet, and other objects. Like unexpectedly encountering the familiar scent of an ex in the metro, the world is constantly obstructing our view with triggers, but the best antidote for this painfully human ailment is to take hold of reality for oneself. Infusing objects with awe and wonder, one becomes able to navigate the unnavigable. Brookbank’s work reminds me of the way in which we transform mundane objects into sacred symbols, which also happens to be the aesthetic gesture par excellence. What is art if not transforming the functional into something aesthetic that helps us make sense of the affective minefield we call life?