Have our lives improved since AI became a daily part of them?

On the closing day of this year’s MUTEK Forum, Dr. Karim Jerbi, psychology professor at Université de Montréal and Canada Research Chair in Computational Neuroscience and Cognitive Neuroimaging, asked the crowd to reflect on the impact that artificial intelligence has had on our daily lives. Is AI really working for us? Is it helping us resolve any of the problems currently affecting our communities?

Photo credit: Maryse Boyce

Of course, everyone’s answers may differ, as artificial intelligence does not play an equal role in everybody’s life and, with its recent and commercial popularization, AI poses real concerns for many individuals—but it is precisely those kinds of concerns that led the discussion during the “Abundant Intelligences at the Intersections of Neuroscience, AI, Art, and Indigenous Knowledge” panel. Prof. Jason Edward Lewis, panel moderator, professor of computation arts at Concordia University and co-director of Abundant Intelligences, spoke about the importance of addressing bias and data sovereignty when creating AI models. He explained that if bias keeps coming up on an AI model, then bias is not simply a bug of the model, but a feature of it—which can only be resolved by building an entirely new foundation. And that is precisely what the Abundant Intelligences team aims to do.

Rooted in Indigenous epistemologies and protocols, Abundant Intelligences aims to revolutionize the world of AI, not only to better represent and support Indigenous communities, but to highlight the wide variety of perspectives and types of intelligence in the world, both human and non-human.

As explained by Dr. Jackson Two Bears, associate professor of art studio and Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Arts Research & Technology at Western University, technological development always threatens to leave Indigenous communities out of the story—a lot of reserves don’t have access to clean drinking water, let alone high-speed internet—so it is crucial that Indigenous voices be included and heard in discussions and developments surrounding AI. In Abundant Intelligences, that entails the collaboration of interdisciplinary researchers, labs, and communities from across the Indigenous world. As a research creation project, Abundant Intelligences encourages cooperation between the sciences and the arts, refusing to let computer science be the sole field to define the ‘intelligence’ part of artificial intelligence—and, as put by Dr. Melanie Cheung, a Māori neurobiologist now getting to work alongside artists, the bridging of the two fields allows researchers to approach science from a more creative angle, expanding the possibilities of what could be achieved.

With the project expected to span until 2029, Jason Lewis explained that most of their work so far has consisted of building a strong infrastructure that will allow their interdisciplinary group to be productive together. This has involved moderating workshops, leading integrations, and spending time together. They’ve also started working on seed projects, including one described by Dr. Jerbi, which aims to create AI models that can record brain signals while dreaming and data mine them for visuals.

Conversations about AI, the ethics surrounding it, and its role in the non-human world continued throughout the rest of the day, as Milieux’s “Wilding AI Lab,” presented in collaboration with the Applied AI institute, presented a day-long series of experiments and provocations encouraging audiences to consider if and how we can make AI wild again. Held in Monument-National’s Studio Hydro-Quebec, attendees were encouraged to talk among themselves, exchange ideas, and interact with the lab’s various experiments and prototypes, including those presented by the inaugural cohort of the Machine Agencies GenAI Studio.

One of the Lab’s provocations was given by Dr. Fenwick McKelvey, co-director of the Applied AI Institute, and Dr. Bart Simon, director of the Milieux Institute for Arts, Culture, and Technology. Their provocation encouraged listeners to think of AI as a “craftwork” that should be appreciable as a means, not an end. As they put it, AI should be about “play, not simulation,” and “endurance, not speed.” In that spirit, they explained that members of the GenAI studio were advised to use local and open-source AI models when possible, leaving commercial models as a last resort, and thus introduced the next section of the event. As the microphone was passed around the room, we got to hear about the six projects being developed by the inaugural members of the Machine Agencies GenAI studio.

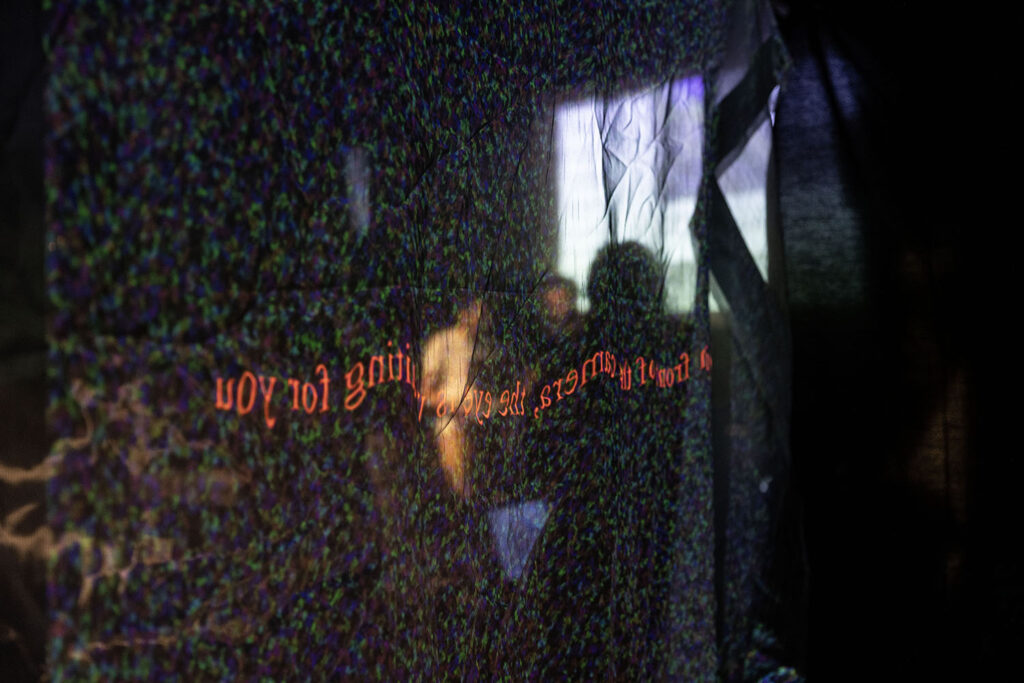

The first project to be presented was Aurélie Petit’s B̷l̷a̷c̷k̷ ̷P̷u̷d̷d̷i̷n̷g̷; inspired by Black Pudding (1969), the earliest animated adult film to be directed by a woman. Since the film is now considered to be lost media, Petit used existing summaries, reviews, and interviews with Nancy Edell, director of the film, as guiding prompts to generate AI images. These images, along with their accompanying prompts, were all compiled into a website that attendees could peruse, letting us analyze and question the ethical and creative limits of generative AI, especially when reproducing sexual images. For instance, it became evident that AI’s understanding of what a woman looks like is extremely narrow, as the bodies portrayed in the images were exclusively white, thin, and cisgender, despite never being instructed to represent them as such. By relying on these flawed recreations, B̷l̷a̷c̷k̷ ̷P̷u̷d̷d̷i̷n̷g̷ also highlights the lack of conservation that is afforded to the animated and/or erotic works made by and for women.

The presentation continued with Kamyar Karimi’s Deconstructed Selfies: Regenerated. By asking participants to take selfies with a specific AI model, which would then complete an emotional reading of their face and reproduce a more colorful, deconstructed version of the original image, the project aims to explore the ways people represent themselves online, how AI represents those same people, and what the future of selfies may look like.

We also got to see François Lespinasse’s Mechanical Meanderings, which uses written and visual inputs to form audiovisual landscapes and backgrounds; Rowena Chodkowski & Hamidreza Nassiri’s Machine Dreams of a Cosmopolitan Past, which asks generative AI to reproduce Iranian miniatures and explores how cultures will continue to evolve in this new digital age; and Luciano Frizzera & Maurice Jones’ The Consultation Machine, a sarcastic tool that aims to revolutionize public consultation by asking users to fill out a prompt, Mad Libs style, that will then generate a letter to elected government officials on a particular issue.

Last but not least, we were introduced to Maurice Jones’ feral.ai, a local AI model that can run independently, listening and reacting to auditory input in order to generate various diary entries that opinionatedly describe the sounds heard throughout the day. The project’s goal is to witness the growth that may occur from repeated and ongoing interactions with the sound agent, and to determine how to deploy AI programs carefully and responsibly.

After a couple of additional provocations, as well as some closing calls to action, the “Wilding AI Lab”—and the 10thedition of the MUTEK Forum—came to an end, letting attendees reflect on the day’s discussions and experiments; we were left to ponder what it means to be human in a hyper-digital world, as per the theme of this year’s Forum, “Utopia or Oblivion: Crafting Human-Centered Technological Futures.” As humans exploring the limits and possibilities of digital culture and artificial intelligence, how can we hold ourselves accountable to both human and non-human realities? What more can we do to protect our natural environment, as well as the rights and freedoms of artists? The many events of the day cracked these questions open, and proposed different solutions to tackle them, but it remains to be seen how they continue to deal with such problems as they arise. It may be important to keep asking, have our lives improved since AI became a daily part of them? And, if not, could we still make it so?

Text by Paola B. López Sauri