What if we can build new and different forms of solidarity

with our objects (and they with us)? And what if, beneath

the nose of scholarship, this is what we do every day?

– Steven Jackson, “Rethinking Repair”

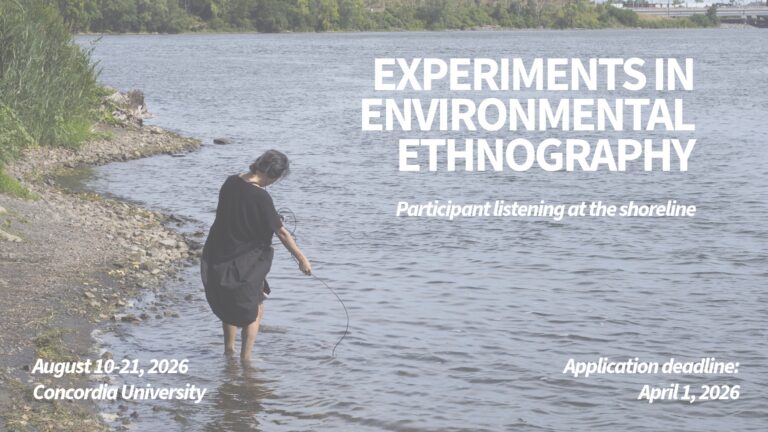

When asked to imagine a graduate methods course, one tends not to think of soldering stations, three foot tall Tetris controllers, or tiny solar robots splashing paint at a canvas. Yet, that’s precisely what we saw at the Milieux Summer Institute during a two-week, interdisciplinary research course aptly named Mess and Method.

Designed by Dr. Darren Wershler, the course gathers students with varied research interests from different departments and encourages them to move beyond textual analysis toward a methodology that foregrounds collective, experiential learning. This year’s installment was co-taught by Dr. Lai-Tze Fan, the Canada Research Chair in Technology and Social Change (SSHRC Tier 2) and Director of the U&AI Lab at the University of Waterloo. Joining them were guest lecturers Steven J. Jackson (Cornell University), Alice Jarry (Concordia University), and Phil Reilly (Right to Repair), as well as research assistants Zeph Thibodeau, Mario Gaudio, and myself, who served as project facilitators.

Mess and Method launched with an online seminar to establish the theoretical context for the hands-on work that would take place at the Milieux Institute the following week. Operating on Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s principle of generous thinking—an approach that charges academia to temper its penchant for criticism and competition—the course foregrounds collaborative knowledge sharing and skill transfer. During an initial round of icebreakers, Darren tasked us each to list one of our skills with the proviso that it had to be something we use outside the academy. This question altered the tenor of the typical Zoom classroom, encouraging us to bring more of ourselves to the conversation.

The initial theoretical foray explored themes of maintenance, repair, and sustainability through the lens of affect, justice, temporality, and scale. Students led discussions on each of the readings, tying the works to their own interdisciplinary research interests. In the afternoons, guest lecturers open-handedly shared everything from the design process behind site-specific, art installations about dust to practical tips for repairing washing machines.

The seminar was uniquely compelling, insightful, and messy. Supplemental to the verbal discussions on Zoom was a robust backchannel on the course’s Discord server, replete with memes and emojis. The decentralized classroom radically transformed the seminar model, affording students the opportunity to pick up threads from earlier in the conversation, elaborate on each other’s points, or express sentiments of care and solidarity on a platform where the pace of conversation moved differently. While this non-linear text-based chat wasn’t the most accessible medium for some learners, others found themselves deeply appreciative of the rare opportunity to engage in chaotic, synchronous discourse. The class structure itself revealed and challenged the way academicinstitutions privilege some approaches to learning over others and was one of many instances of incommensurability that permeated the course.

After a weekend to rest (we encouraged everyone to take time to recharge before embarking on the next stretch of this intensive), the class gathered in the Milieux Makerspace. Against the backdrop of power tools, 3D printers, and sewing machines, students began to put theory into practice. It was here that we could feel out for boundaries and identify opportunities in our knowledge frameworks.

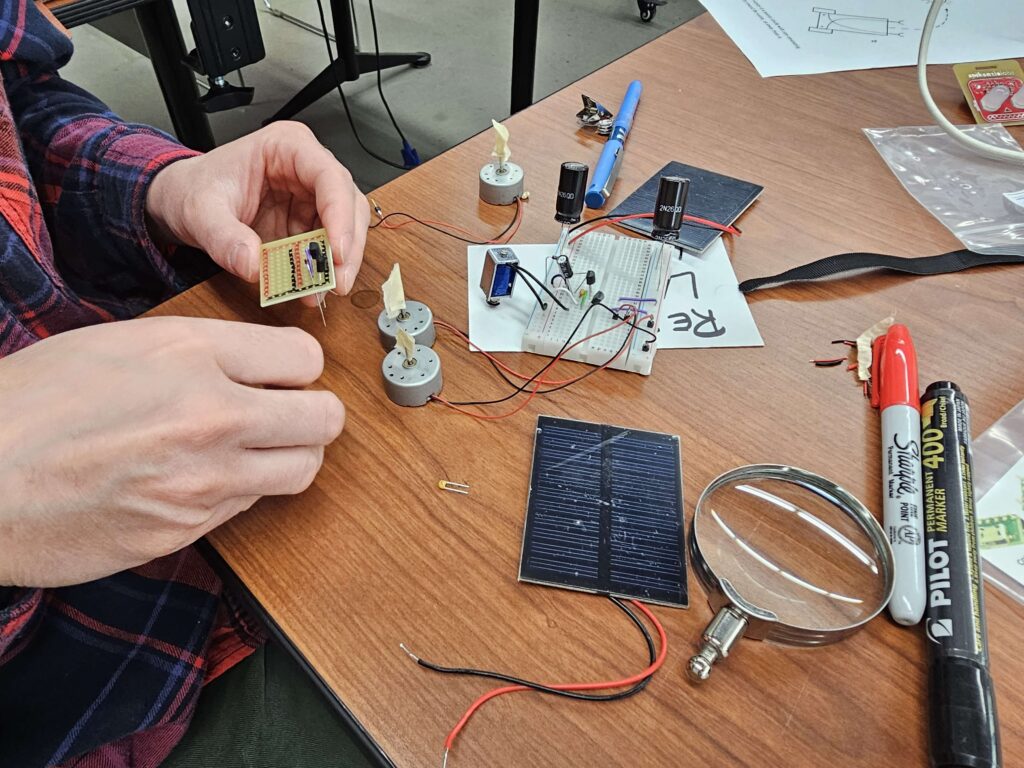

Our in-person icebreaker saw students building their own battery-powered blinking robot badges. These small, beginner-friendly kits offered an easy entry point into soldering. Perhaps most importantly, it helped dispel some of the anxieties of walking into a Makerspace without any prior DIY experience.

Adorned with newly illuminated wearables and motivated by a quick victory, the class broke into four groups to begin working on their collaborative projects. Each project was supervised by a facilitator, but the research questions, practical approaches, and exchange of research findings were driven by the students themselves.

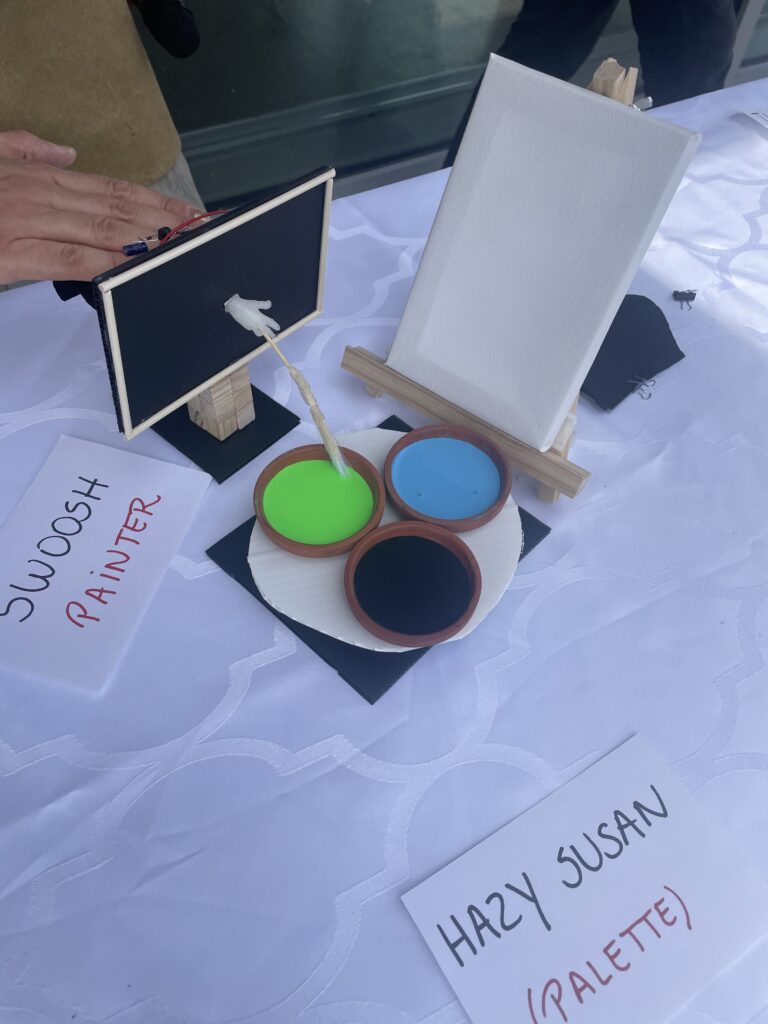

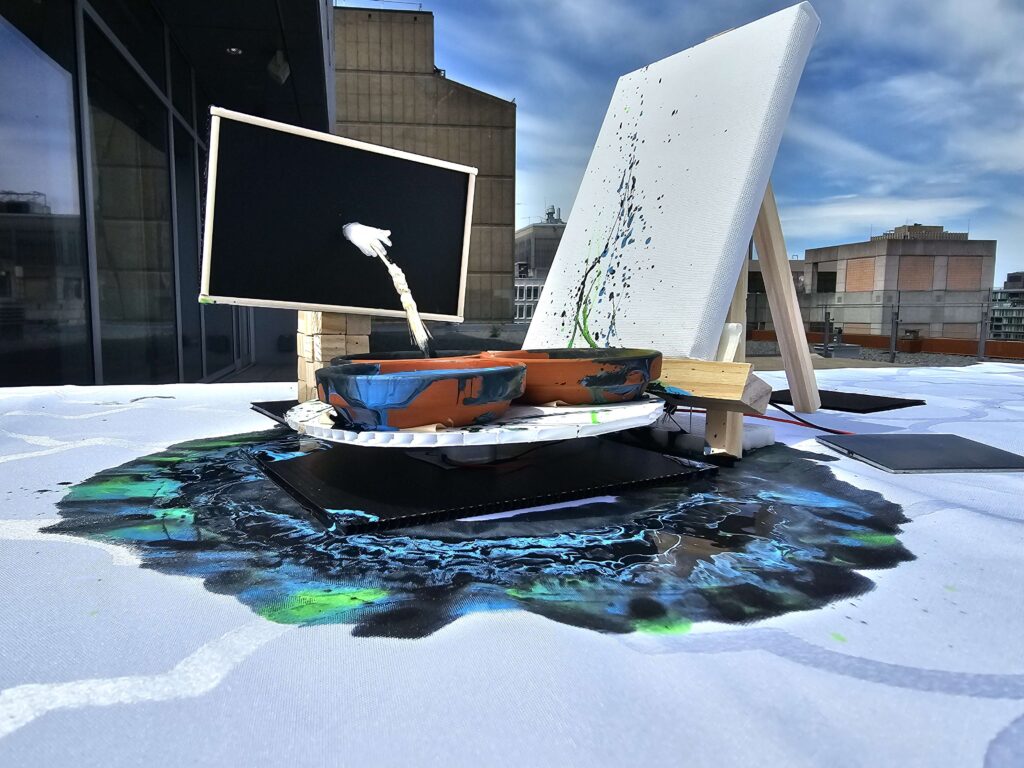

- Zeph’s group explored embodied intelligence and socio-material relationships through the construction of tiny, solar-powered robots. Beginning with a simple BEAM design, the group co-created an artist collective of eight robots who put on a dynamic, colorful performance at the class’s closing colloquium.

- Lai-Tze’s group explored human- and computer-based methods for identifying and mitigating bias in datasets. Rather than focusing on the approaches of science and technology studies, the group considered how humanities and social science skillsets can be leveraged to contribute to data science.

- Mario’s group modified (or “modded”) the sound and video output of an ostensibly unremarkable Sega Genesis II from the 1990s, allowing it to work on contemporary screens. The group grappled with the tension between exploratory research and the expert knowledge formed within interpretive modding communities.

- Finally, my group set out to challenge the universalization of experience embedded in videogame controller design. Over the course of the week, Catherine, Julia, Kayla, and Rachael reflected on their own relationships to videogames and challenged the hegemony of play through the construction of an immense, cooperative Tetris controller.

Through direct engagement with material cultures, these interdisciplinary projects all revealed the way learning is an ongoing, collaborative process that is highly dependent on skill sharing and knowledge exchange. My group alone drew on the expertise and generosity of so many others, including Marc Beaulieu (Milieux’s Head of Technical Support and Infrastructure), the researchers at the wood and metal shops, and the folks at the Concordia University Centre for Creative Reuse (CUCCR), which we visited on Tuesday afternoon to scavenge for spare parts. Together, the groups navigated some of the limits of the theories we had read and acknowledged some of the critical omissions of single-author research.

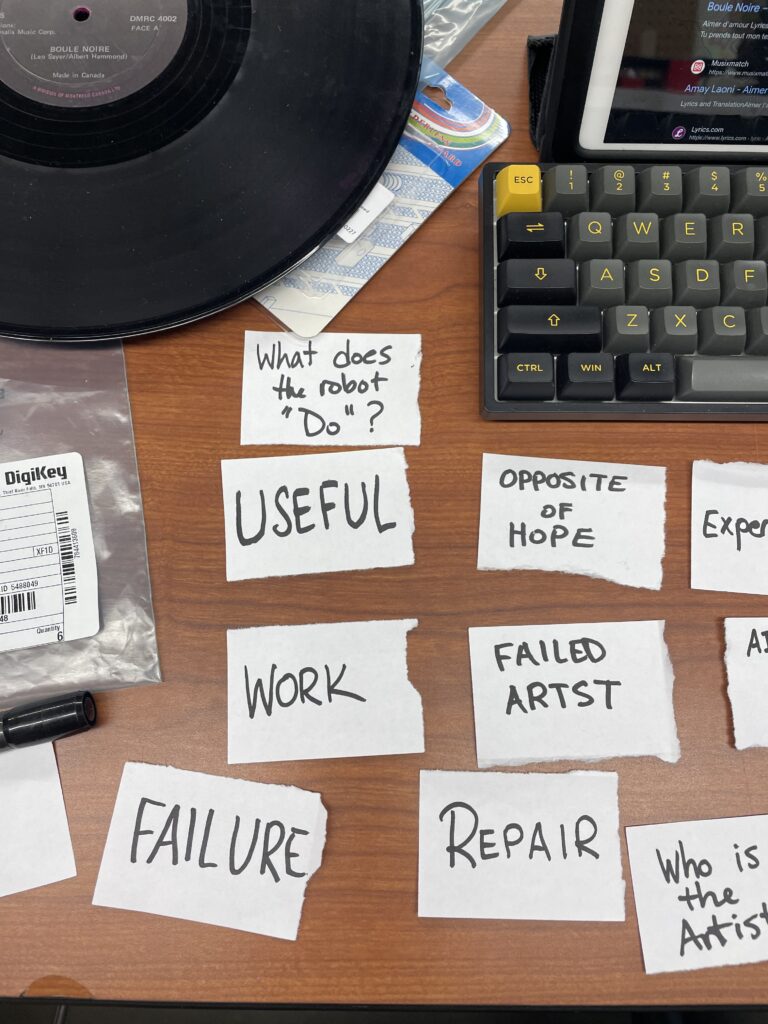

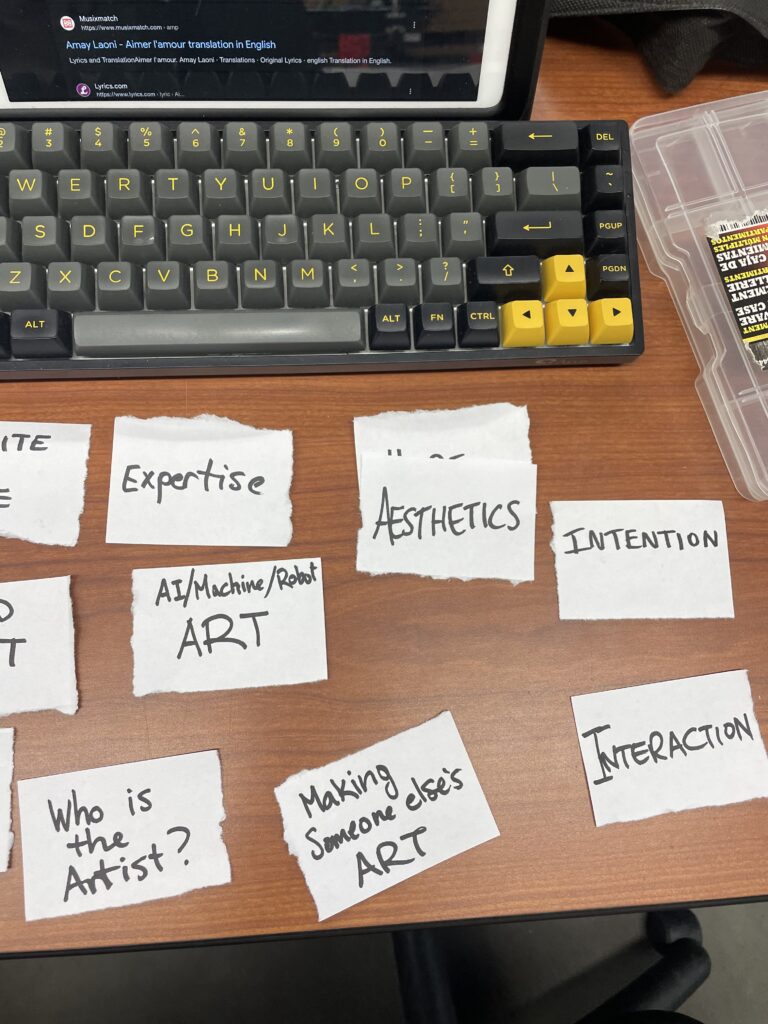

Photo credit: Alex Custodio

Guiding each of the projects was Darren’s heuristic for the course, a loose set of problem-solving approaches that has emerged from hands-on experience. This recursive approach considers subjects, objects, knowledge cultures, infrastructures, and policy, all while remaining mindful of the incommensurabilities that underlie this work. The techniques we look at—from hardware modding to dataset training—shape and are shaped by communities of practice, each with their own technical, discursive, and affective approaches. The course offers a rare opportunity to reflect not only on objects but also on our relationship with them as scholars and people. What emerged in the class’s final colloquium was a common throughline of care and the often-invisible labour that goes into care work. What does it mean to care for a collective of tiny solar robot artists? What does it look like to check in with each other after an afternoon spent mired in the racist, transphobic, sexist data of AI datasets? Why do conversations around modding seldom acknowledge the slow, meticulous work of cleaning a circuit board? How do we leverage each other’s strengths to create a cooperative process and experience? All these questions point to acts of maintenance.

Photo credit: Alex Custodio

This session marked my fourth year participating in this course. When I enrolled in it as an MA student in 2017, I’d never used a soldering iron, nor had I ever modded anything. I credit the playful, exploratory, transformative pedagogy of this course for much of the work I do now in my PhD, where I run workshops, develop tutorials, and perform forensics of residual videogame hardware together with friends and colleagues.

Educational institutions privilege individual knowledge development and dissemination, but Mess and Method challenges the viability of this model. In its place, the course engages students in hands-on, collaborative, interdisciplinary research that recognizes how learning is an emergent process. It emboldens us to do research differently, drawing less on an ethos of do-it-yourself than of do-it-together—generatively, messily, and without fear of failure.

Text written by Alex Custodio, PhD student in Humanities at Concordia University.